|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub. Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub.

Jean Gebser's blindspotThe Chinese PerspectiveJan Krikke

When Swiss philosopher Jean Gebser, in his book The Ever-Present Origin, argued that the invention of linear perspective during the Italian Renaissance marked a new stage in human consciousness, he overlooked a remarkable precedent: a projection system developed in China centuries earlier. That omission has shaped how the modern West understands both art and consciousness. The story of axonometry, the “other” perspective, reveals how the Chinese integrated space and time long before Europe's perspectival awakening — and how that visual grammar resurfaced in twentieth-century modernism.

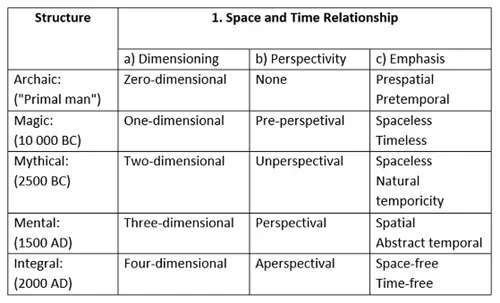

Figure 1 — Structures of Consciousness and Space-Time

Jean Gebser's model of consciousness structures aligns the evolution of human perception with spatial dimensioning. The transition from the perspectival “mental” structure to the aperspectival “integral” marks the reemergence of non-linear, simultaneous space—paralleling the shift from Renaissance perspective to modern and East Asian modes of depiction. From Vanishing Point to Flowing SpaceLinear perspective, devised in the fifteenth century, created the illusion of depth by converging parallel lines at a vanishing point. This optical geometry gave rise to a worldview centered on a single observer — the hallmark of the Western “mental” structure Gebser celebrated. Yet by the eleventh century, Chinese painters and architects had already developed an alternative system, known as dengjiao toushi, or “equal-angle see-through.” It depicted forms without convergence or distortion created by the vanishing point, allowing space to extend freely in all directions. Unlike perspective, which freezes vision in a single moment and position, Chinese axonometry unfolds as a continuum. In the hand-scroll format — a seamless horizontal painting viewed by slowly unrolling it — the eye travels through a landscape that combines multiple moments and viewpoints. The image becomes a journey through space-time, not a snapshot of it. The observer is not fixed but participates in the flow. This integration of movement and duration foreshadowed what modern physics would call the unity of space and time. Where Renaissance artists “discovered” the three dimensions, the Chinese were already painting in four.

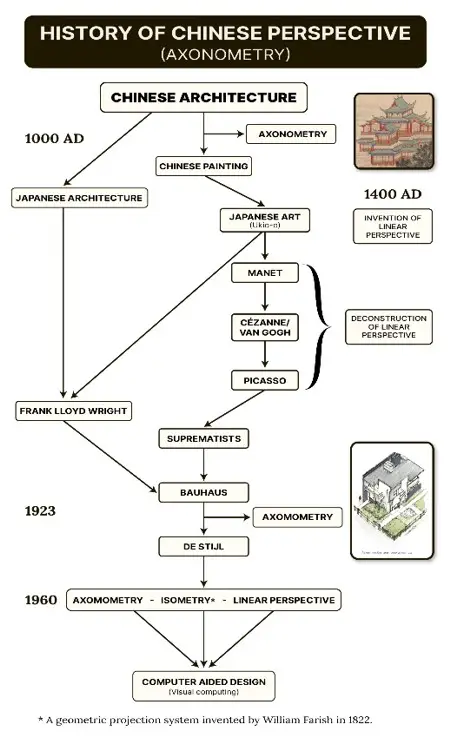

Figure 2 — Evolution of spational representation

The Chinese system of axonometric projection—a method of depicting space without a vanishing point—spread to Japan, influencing Ukiyo-e art, which later inspired Manet, Cézanne, and Van Gogh to move away from optical pressentation through the deconstruction of linear perspective. By the 1960s, axonometry, isometry, and linear perspective merged in Computer-Aided Design and other digital visualization tools of visual computing, linking an ancient Chinese geometry to the foundations of modern design. From East to West: The Hidden TransmissionAxonometry reached Europe through Jesuit intermediaries in the eighteenth century, who brought Chinese drawings home as curiosities. European draftsmen adapted the technique for technical illustration, where its lack of optical distortion proved invaluable. In 1822, the British scientist William Farish codified the mathematical basis of axonometry in his invention of isometry — a projection system of “equal measures” that preserved true proportions without recourse to the vanishing point. Farish's innovation coincided with the Industrial Revolution's demand for precision. Machine parts, weapons, and architectural plans required measurable accuracy, not optical illusion. Yet the aesthetic implications of this “non-perspective” remained unrecognized until the early twentieth century, when the modernist avant-garde discovered it. The Modernist RediscoveryBy the 1910s, European art and architecture were undergoing a radical reorientation. The Japanese woodblock print (ukiyo-e), itself based on Chinese axonometric principles, had already transformed Western painting. Artists such as Manet, Cézanne, and Van Gogh eliminated chiaroscuro and undermined linear depth, seeking the immediacy of flat yet dynamic space. Cézanne began to tilt and overlap objects seen from different vantage points; Picasso pushed further, fusing multiple viewpoints within a single form — the birth of Cubism.

Figure 3 — Picasso and the Deconstruction of Perspective

In Picasso's analytic Cubism, multiple spatial planes coexist simultaneously. The perspectival observer dissolves, replaced by a dynamic interplay of viewpoints—an echo of Chinese and Japanese spatial logic. Critics like Guillaume Apollinaire surmised that these experiments paralleled Einstein's newly formulated space-time continuum. Jean Gebser, living in Paris among the Cubists, interpreted their fragmentation as the expression of a new “aperspectival” consciousness — an awareness of time entering art. Yet he never connected that insight to the earlier Chinese synthesis from which this non-perspectival vision ultimately descended. In architecture, the same transformation occurred. Modernists such as Theo van Doesburg, Gerrit Rietveld, and El Lissitzky adopted axonometry for their plans and renderings. De Stijl architects used it not merely as a technical device but as a language of modernity — a projection without hierarchy, without “near” or “far.” By 1923, axonometric drawings were exhibited in Paris as visual manifestos for a new architecture based on structural transparency and spatial logic. The aesthetic of the machine had found its medium. Space as MediumIn 1912, the Austrian-American architect Rudolph Schindler famously declared: “The architect has finally discovered the medium of his art: SPACE.” This statement marked a conceptual revolution. For centuries, European academies had treated architecture as a sculptural art — form carved in matter. Schindler and his contemporaries redefined it as the shaping of voids. “Space,” once an abstract notion, became tangible, livable, and aeshtetics.

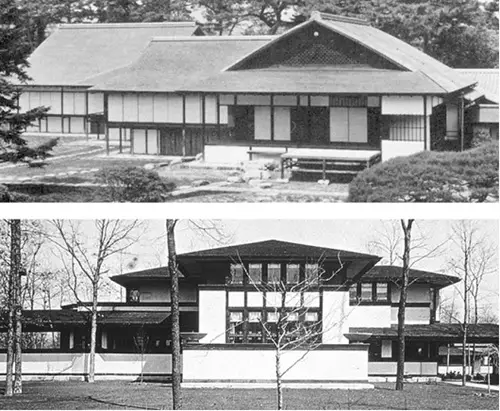

Figure 4 — Japan and the Discovery of Architectural Space

Top: Katsura Imperial Villa, Kyoto (17th c.). Bottom: Frank Lloyd Wright, Winslow House, 1893.

Japanese modular design and fluid interior-exterior relations influenced Wright's redefinition of architecture as the art of shaping space rather than mass, foreshadowing modernist spatial thinking. Frank Lloyd Wright carried this transformation further. Deeply influenced by Japanese architecture, he saw buildings as configurations of continuous space rather than enclosed mass. “The Japanese house, with its sliding screens, gives a unique sense of movable space,” he told his apprentice Edgar Tafel. Wright even linked this insight to Lao Tzu's dictum about emptiness: “The reality of the building does not consist in the four walls and the roof, but in the space within.” Thus, through Japan, Chinese spatial philosophy entered the bloodstream of Western modernism. The architect's discovery of space echoed the Chinese painter's ancient awareness that emptiness is the essence of form. Claude Bragdon and the Aesthetic of the Mind's EyeThe first Western theorist to appreciate the aesthetic dimension of axonometry was the American architect Claude Bragdon, whose 1932 book The Frozen Fountain described isometric projection as “more faithful to fact than to appearance.” Bragdon intuited what Gebser would later call aperspectival consciousness:

“Parallel lines are really parallel; there is no far and no near… Isometric perspective shows things as they are known to the mind. It renders the mental image — the thing seen by the mind's eye.”

For Bragdon, axonometry visualized not perception but cognition — how the mind imagines objects in thought. It was, in his words, “more intellectual, more archetypal.” Long before digital design, he grasped that geometry could model mental as well as physical space. From Blueprint to AlgorithmBy mid-century, axonometry had become the lingua franca of modern design. Every architect and engineer now begins with it; every computer-aided design system depends on it. In that sense, axonometry prefigured the digital paradigm.

Figure 5 — Axonometry and the De Stijl Vision

Gerrit Rietveld's Schröder House (1924) rendered in axonometric projection. De Stijl architects embraced axonometry not as a technical convenience but as a visual language of pure spatial relationships—non-hierarchical, rational, and dynamic. Like the pixel grid, axonometry abstracts the world into measurable relations rather than visual impressions. It transforms the subjective eye of Renaissance perspective into an objective interface — a worldview of systems and networks rather than appearances. This technological dominance ironically vindicates the Chinese conception that had once been dismissed as “non-scientific.” The modern world now thinks in the very projection that Chinese artists conceived a millennium ago.

Figure 6 — From Scroll to Screen: Axonometry in CAD

Above: Axonometry in Ukiyo-e composition. A Japanese multi-storey interior rendered in axonometry. The absence of a vanishing point allows simultaneous depiction of multiple rooms and actions, embodying narrative time within spatial continuity.

Below: Computer-aided design systems adopt axonometric projection as their default spatial framework. What began as a Chinese method for visualizing relational space has become the universal grammar of digital architecture and design. A Lost Continuity RestoredGebser's claim that Europe's perspectival consciousness opened the three-dimensional world was not wrong, but it was incomplete. The history of axonometry shows that another pathway existed — one that united rather than divided the observer and the world. Through axonometry, the Chinese achieved what the West only later sought through Cubism, relativity, and digital simulation: a vision of reality beyond the confines of a single point of view. In rediscovering that lineage, we uncover a hidden genealogy of modernity. The “machine aesthetic” of De Stijl and the space-architecture of Wright were not spontaneous Western breakthroughs but the culmination of a global dialogue across centuries. In this light, Gebser's “aperspectival” is not an innovation but a return — the re-emergence of an ancient, integrative way of seeing. Long before computers made it universal, the Chinese had already imagined the world as a seamless, unfolding field of relations — a cosmos without vanishing points.

|