|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub. Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub.

From Factory to AshramIndia's Role in the Post-Work EraJan KrikkeFor centuries, work has been humanity's main source of meaning. Identity, purpose, and social status have been tied to what people do for a living. But as artificial intelligence and robotics advance, we approach a turning point in history: a time when machines will perform most forms of labor—manual, intellectual, and even creative. When that happens, humanity will enter a new stage of evolution, one that macrohistorian Lawrence Taub called the Spiritual-Religious Age II. In this emerging world, India, not China, is poised to become the most influential nation on Earth—not through economic or military power, but through the depth of its spiritual and philosophical heritage. Taub (1938-2018) foresaw that AI, robotics, and free energy would eventually liberate humanity from routine labor. At first glance, this seems utopian: material needs satisfied without toil, poverty eradicated, and abundance generated by machines. But Taub also warned of an existential vacuum. Work, especially in the industrial and post-industrial eras, has provided people with identity. As he noted, even political leaders are judged by “job approval” ratings; the very language of governance presumes that life's purpose is labor. When work disappears, so does a key pillar of self-definition. People will no longer be “engineers,” “teachers,” or “drivers.” The social contract built around wage labor—education, employment, retirement—will dissolve. China's Material PeakChina's rise exemplifies the Worker Age. Its Confucian work ethic, meritocratic bureaucracy, disciplined labor force, and "teamwork capitalism" have lifted more than a billion people from poverty. But China's strength—its ability to mobilize millions for collective tasks—may become a weakness in the post-labor world. A society built around industriousness and hierarchy may struggle to adapt when industriousness is obsolete. The state's legitimacy rests on delivering economic growth; when automation saturates productivity, that legitimacy will wane. Moreover, China's philosophical heritage, rooted in order and stability, is less equipped to address the inner void that follows the end of work. Confucian ethics regulate behavior within society; they do not easily answer the question of why one exists when social roles vanish. If China represents the outer mastery of matter, India represents the inner mastery of mind. Taub predicted that when work loses its centrality, humanity will turn inward to seek purpose. “No longer able to identify with their profession,” he wrote, “people will turn to spiritual pursuits for meaning, direction, and communion”

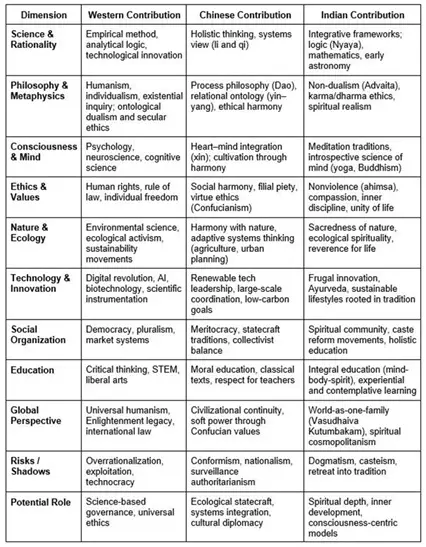

Fig. 1. Contributions from the three main "source cultures."

This is precisely where India's millennia-old traditions—Vedanta, Yoga, and the science of consciousness—become relevant on a planetary scale. Unlike most civilizations, India never divorced metaphysics from daily life. The Upanishads explored the nature of consciousness long before modern neuroscience; the Bhagavad Gita taught the art of detached action, a guide for a world where outcomes are increasingly automated.

While China perfected material coordination, India cultivated interior technologies: meditation, mindfulness, and the refinement of perception. These are precisely the faculties that the post-work world will need. In the coming century, influence will not derive from the power to manufacture goods, but from the power to interpret existence. AI can produce outputs; it cannot confer meaning. When material needs are met by machines, people will seek teachers, guides, and frameworks for inner growth. India already exports these in abundance—yoga studios, meditation apps, and spiritual retreats form a global industry valued in the hundreds of billions. Yet beneath the commercialization lies a deeper current: the recognition that Indian thought offers an integrative philosophy of consciousness suited to the dilemmas of the digital age. Taub and other contemporary thinkers, such as Ken Wilber, believe we are at the dawn of a new Religious-Spiritual Age in which people start to look at reality more holistically. The last such age was prehistory, characterized by animism. Humans and nature were seen as inseparable. The new spiritual age will integrate and transcend the achievements of all previous ages—science, technology, and individual autonomy—into a new spiritual synthesis. Machines will do routine work, leaving humans to engage in creative and contemplative pursuits. Taub predicted a change in humanity's mindset: a “religious-spiritual capitalism” encourages the exploration of consciousness rather than consumption. India's civilizational DNA aligns perfectly with this transition. Its philosophy already bridges the material and spiritual, teaching that the world is both real and divine—maya and Brahman. Its social structure, though historically distorted, embodies the recognition that different people have different callings, an idea that can be reinterpreted ethically in a post-work society as diversity of purpose rather than hierarchy. The New Meaning EconomyAs automation spreads, economic value will shift from production to experience—from making things to cultivating states of being. This “meaning economy” will prize wisdom, creativity, and empathy. AI can simulate intelligence, but not insight. The human faculties that remain irreplaceable—intuition, imagination, moral judgment—are precisely those that Indian philosophy has long explored. In this sense, the future global culture may become Vedantic rather than technocratic. Western humanism placed the self at the center of the universe; Chinese Confucianism emphasized social harmony; Indian Vedanta dissolves both into a unity of consciousness. Such a worldview can reconcile the digital and the spiritual, the individual and the collective. It can also offer a moral framework for governing intelligent machines by viewing them not as competitors but as extensions of consciousness, instruments of a larger unfolding.

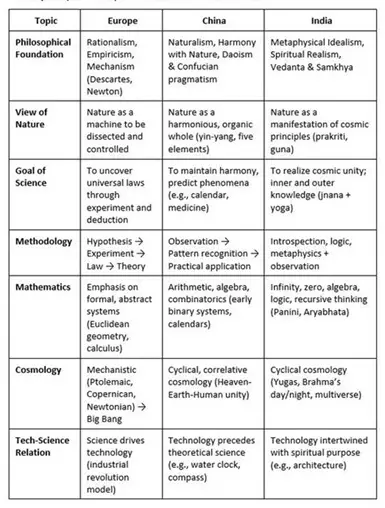

Fig. 2. Classical view of science in Europe, China, and India

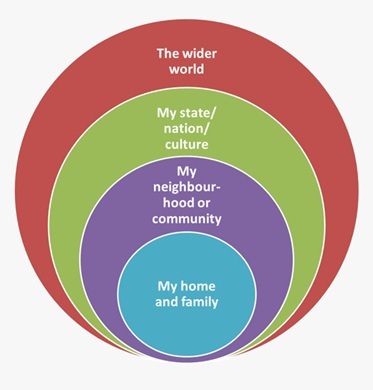

Collective EvolutionArtificial intelligence will not merely change economies; it will redefine what it means to be human. AI acts as both mirror and catalyst, confronting us with our own creations and forcing us to assume responsibility for them. India's traditions of karma and dharma—action and duty—may offer the ethical vocabulary for this new stage. Karma reframes causality in moral rather than mechanical terms: every act has consequences that shape consciousness. Dharma reminds us that freedom without responsibility leads to chaos. These ideas could become the philosophical infrastructure for an AI-governed world, guiding policy and personal conduct alike. China's techno-teamwork model, though efficient, risks reducing ethics to compliance. India's pluralism and tolerance for paradox—its ability to hold contradictory truths—make it a more adaptable moral ecosystem for the age of autonomous systems. That being said, China is currently building the systems and the "hardware" that will be needed for the post-material era. Taub differentiated between power and influence. Power coerces; influence inspires. The 21st century will belong not to the nation with the largest GDP but to the civilization that offers the most coherent vision of human flourishing beyond work. China's “Digital Silk Road” extends infrastructure; India's emerging “Spiritual Network” extends insight. The two are not mutually exclusive—India will continue to adopt technology, and China will cultivate spirituality—but their emphases differ. Already, India's digital transformation coexists with a renaissance of philosophical discourse. Its massive youth population, educated in technology yet steeped in cultural continuity, forms a unique bridge between the algorithmic and the spiritual. Indian engineers design the AI systems that will automate labor, while Indian thinkers, teachers, and artists explore how humanity can live meaningfully once most labor ends. These currents converge today in a global search for a balance between rich and poor, male and female, material and spiritual, this-worldly and other-worldly. India, as a civilization that has long embraced synthesis rather than dichotomy, is well-positioned to lead this integration. As the world shifts from competition to cooperation, from accumulation to awareness, India's soft power will rise. Its influence will not be imperial but inspirational. Just as the West once exported technology and China now exports infrastructure, India will export meaning. Its universities may teach consciousness studies alongside computer science; its cities may become hubs for spiritual innovation, where AI and ethics co-evolve. The 19th century conquered nature, the 20th century conquered information, and the 21st century will conquer the self. The frontier is no longer outer space but inner space—the exploration of awareness itself. In that domain, India has a head start. When machines perform every task, humanity will face the ultimate question once posed in the Upanishads: Who am I? The civilization best equipped to answer that question will lead the world. China mastered production; the West mastered innovation. India's mastery lies in consciousness. In the coming post-work era, when productivity is automated and meaning is scarce, that mastery will prove decisive. As Taub envisioned, the world's center of gravity will shift from factories to ashrams, from output to insight, from matter to mind. The materialistic age will give way to the spiritual age, and in that new dawn, India—ancient, plural, and profoundly introspective—will illuminate the path for a civilization learning to live without work and to find purpose within. SynthesisWhen machines have taken over most forms of labor, humanity will not ask how to produce more, but how to live meaningfully. The societies that once defined themselves through productivity will search for purpose. In that post-work world, India—the civilization that has spent millennia studying consciousness—will find itself unexpectedly prepared. Yet India's rise as a global spiritual leader will not come through the assertion of a single ideology or faith. It will depend on the creative convergence of three strands that have shaped modern India: Hindu nationalism, British-derived liberal and socialist traditions, and apolitical Vedanta. Their fusion, rather than their dominance, will determine whether India's spiritual inheritance can become a planetary resource. At present, India stands between two narratives. One is the political confidence of Hindu nationalism, a force that has sought to re-center India's civilizational pride after centuries of colonial subordination. The other is the secular, rights-based framework inherited from British liberalism and European socialism, which continues to underpin the Indian Constitution. Between these poles lies a quieter, older current—Vedanta, the philosophical core of Hindu thought that transcends sect and creed. These three forces coexist uneasily. Hindu nationalism can shade into cultural majoritarianism; liberalism can harden into rootless cosmopolitanism; Vedanta can withdraw into monastic detachment. But in a world where identity is dissolving and work no longer defines self-worth, each contains a fragment of the future: pride, justice, and insight. India's challenge is to turn tension into synthesis. The global era of recent decades promised integration but often delivered alienation. Globalism flattened cultures into markets, and many nations, including India, reacted by reaffirming rooted identities. Nationalism is a reaction to ungrounded globalism. Spiritual leaders, among them Sadhguru, have championed a concentric responsibility that offers a moral geometry for the future. One's first duty is to oneself, then one's family, community, nation, and finally the world. Each wider circle becomes meaningful only when the inner circles are tended. Applied politically, this becomes a blueprint for rooted cosmopolitanism. India's leadership will not come from preaching universalism but from demonstrating that genuine global care begins with local coherence. A nation that has healed its internal fractures, reduced poverty, and built psychological well-being into governance will have moral authority beyond diplomacy or GDP.

Fig. 3. Concentric circle of responsibility

The transition to spiritual leadership requires reconciling the political India, the constitutional India, and the contemplative India. Its positive impulse is the restoration of dignity: the sense that India's spiritual traditions deserve parity with Western rationalism and Chinese collectivism. Yet its danger lies in confusing civilizational pride with cultural uniformity. To mature, Hindu nationalism must evolve from a rhetoric of grievance to a philosophy of stewardship—custodianship of a plural heritage. Pride can be generous: the confident civilization no longer needs enemies. The liberal and socialist traditions of India are the scaffolding that allowed democracy to survive in a continent-sized society. Its moral insight is that freedom, equality, and welfare are preconditions for any higher pursuit. If India forgets these foundations, spirituality degenerates into privilege. A future spiritual state must be secular in administration and spiritual in aspiration: governance grounded in rights, guided by compassion. Vedanta speaks of the unity of existence (Brahman) and the illusory nature of separateness (maya). It is not political but profoundly practical: it teaches the integration of thought, emotion, and action. In the post-work era, where machines perform instrumental tasks, Vedanta offers a "grammar of consciousness"—a way to explore attention, empathy, and self-transcendence as human frontiers. By translating this insight into civic education rather than religious instruction, India can turn spirituality into a public good.

|