|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub. Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub.

The "Spirit" of Yin and YangA Path to a Global EthosJan Krikke

The term spirituality, derived from the word spirit and widely used in contemporary society, means different things to different people. The closest Chinese equivalent to the word spirit is qi (ch'i), variously translated as cosmic breath, life force, or ether. Sinologist Joseph Needham referred to qi as matter-energy. Qi refers to the (magnetic) tension between the cosmic polarities of yin and yang. It covers both physical and intangible phenomena. Confucius, inspired by the I Ching (Book of Changes) applied to yin-yang in the development of his social construct. He gave qi an ethical connotation. William Irwin Thompson (1938-2020) believed the classic Chinese worldview is valuable to modern societies. He argued that the Chinese approach to transcending binary opposites could help us move beyond the divisive ideologies of modernity and create a pathway to a global ethos based on reciprocity.

The Chinese view of Creation: "When the yin and the yang, initially united, separated forever, the mountains poured forth water."

SpiritThe notion of "spirit" has its roots in prehistoric animism. Early humans referred to unseen forces and natural phenomena as spirits. Animism assumed that everything in nature—trees, rivers, animals, inanimate objects—was interrelated and possessed a life force of "spiritual essence." Spirits interacted with humans and required respect, rituals, and offerings. The perception of what spirit means evolved over the centuries. After the emergence of civilizations and religions in early history, humans developed personified gods. In polytheistic religions, spirits often took the form of gods, demigods, or nature spirits. They were associated with specific phenomena like the sun, sea, fertility, or the underworld. In Greek and Roman mythology, spirits (daimons in Greek, genius in Roman) were intermediaries between gods and humans. The Latin word spiritus, meaning "breath" or "air," stems from the Proto-Indo-European root spes- or spir- meaning "to blow" or "breathe." The notion of spirit was remarkably similar in different cultures. In Sanskrit, spirit can mean prana -- "life force", "ether" or "vital breath." A related word, sakti, is the dynamic energy present in the universe. The latter is often personified as the divine feminine principle. In both Hebrew (ruach) and Greek (pneuma), spirit is translated as "breath" or "wind." It conveys the idea of God as the source of all life and vitality. He breathes life into humanity (e.g., Genesis 2:7). In Africa, the Yoruba concept of Ase (pronounced "ah-shay") represents the spiritual power that enables creation, transformation, and connection between the physical and spiritual realms. Bantu-speaking peoples often describe life as infused with ntù, a vital force that flows through all beings and objects. Plato and Aristotle associated spirit with the human soul and its connection to rationality and the divine. Plato described the soul as immortal and the seat of reason, emotion, and desire, alluding to a dualistic nature between spirit and body. Aristotle viewed the soul (psyche) as the form of the body, integral to its existence rather than separate. In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, spirit is often linked to the divine -- the breath of God, a life-giving force, and a connection to the transcendent. Christianity expanded the concept of spirit with the doctrine of the Holy Spirit. It emphasized a divine presence active in the world and the lives of believers and introduced ideas about spiritual salvation, eternal life, and moral responsibility. Augustine and Aquinas integrated spirit with theology and philosophy. Spirit was typically distinguished from matter, emphasizing its immaterial and eternal qualities. The growing emphasis on reason and science during the Enlightenment led to a more secular view of spirit, often discussed in psychological or metaphorical terms. In modern philosophy and psychology, spirit is often associated with human consciousness, creativity, or vitality. Kierkegaard and Heidegger explored the spirit as an aspect of individual authenticity and freedom. Spirit was gradually stripped of religious connotations. More recently, philosophers have interpreted spirit in social terms. Jürgen Habermas advocated for a "post-metaphysical philosophy." Spirituality should emerge through ethical and existential conversations rather than metaphysical systems. Charles Taylor proposed that "spiritual fulfillment" can be found "within secular, human-centered frameworks without recourse to the transcendent." Ken Wilber defined spirit in a broad and inclusive way, emphasizing its presence in all dimensions of existence. Similar to Wilber, William Irwin Thompson's notion of spirit is holistic. He integrates personal, cultural, and cosmic dimensions of existence. Thompson sees spirit as a force of creativity and transformation, shaping both the evolution of human consciousness and the broader dynamics of the universe. Metamodernism, the first philosophy of the 21st century, sees spirit as a quality inherent in the world and human experience rather than something entirely transcendent or otherworldly. It embraces spirituality outside of traditional religious frameworks and finds meaning in practices like environmental stewardship, social activism, mindfulness, and artistic creation. Metamodern spirituality leans toward collective rather than personal growth and transformation. It addresses global challenges through a "spiritually-informed" lens of interconnectedness and responsibility. The Chinese notion of spiritThe evolution from animism to religion marked the transition from holism to various forms of dualism. Proto-Indo-European developed concepts about opposites like chaos and order, and dark and light. Zoroaster described a universal battle between Ahura Mazda, "the wise lord of light, truth, and order," and Angra Mainyu, "the destructive spirit of darkness, deceit, and chaos." Zoroaster formalized cosmic dualism into a religious framework. Many scholars assume his work played a role in the development of the monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The Chinese developed a unique form of dualism based on natural (yin-yang) polarities. The world was still seen as a unified whole but was governed by the interaction of complementary opposites. The Chinese codified the yin-yang principle in the I Ching. The Chinese written language suggests that the Chinese associated the yin-yang polarities with magnetism. The character for yin can mean shady, cloudy, moon, and a negative (magnetic) charge. The character for yang can be read as bright, mountain, sun, and a positive (magnetic) charge. The Chinese probably became aware of magnetism during the Zhou Dynasty, when they discovered magnetic stones or lodestones. They used lodestones to develop the first magnetic compass. The so-called "South pointer" consisted of a spoon made of lodestone and a plate marked with the four cardinal directions.

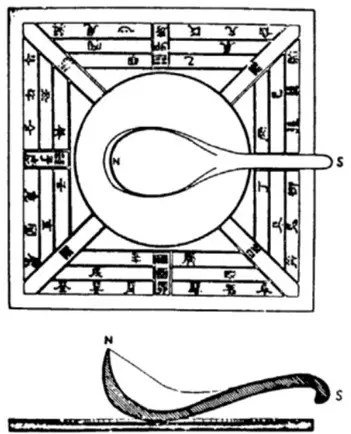

The early version of the Chinese compass or "South pointer." The spoon was made of lodestone.

Another indication that the yin-yang polarities were associated with magnetism is the notion of qi (ch'i), .the tension between yin and yang. Qi is variously translated as "cosmic power," "vital force," and "ether." The Chinese use the radical qi in the compound character for the modern word electricity. The same radical is used in the compound characters for Tai Chi and Qigong. The Eight Trigrams, the basis of the I Ching, also alludes to electromagnetic phenomena. The trigram Zhen represents lightning and is associated with sudden, dynamic energy. The trigram Li symbolizes fire and brightness and is associated with heat. Li represents the qualities of warmth, illumination, and transformation.

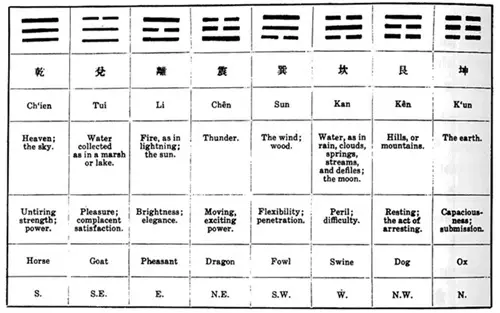

The Eight Trigram and their attributes, eight natural phenomena, and their characteristics or tendencies.

When the Chinese learned about the European invention of electricity in the 19th century, some claimed that the I Ching anticipated the phenomenon of electromagnetism. Lightening was "agitated magnetism." James Legge, who first translated the I Ching into English in the late 19th century, ridiculed the Chinese claims in the introduction of his book. He wrote: "Chinese scholars and gentlemen… who have got some little acquaintance with Western science, are fond of saying that all the truths of electricity, heat, light, and other branches of European physics are in the Eight Trigrams. When asked how, then, they and their countrymen have been, and are, ignorant of those truths, they say that they have to learn them first from western books, and, then, looking into the I Ching, they see that they were all known to Confucius more than 2000 years ago. The vain assumption thus manifested is childish; and, until the Chinese drop their hallucination about the I Ching as containing all things that have ever been dreamt of in all philosophies, it will prove a stumbling block to them, and keep them from entering the true path of science." Unlike Legge, the pioneers of quantum physics of the early 20th century expressed fascination with the Chinese philosophy of nature. Niels Bohr saw parallels between the Chinese worldview and the subatomic world of electrons and protons. Scientist Fritjof Capra, author of the Tao of Physics, pointed out that not everything in life can be captured by empirical science and rational thought. He wrote: "The fact that modern physics, the manifestation of an extreme specialization of the rational mind, is now making contact with mysticism, the essence of religion and the manifestation of an extreme specialization of the intuitive mind, shows very beautifully the unity and complementary nature of the rational and intuitive modes of consciousness; of the yang and the yin." Systematizing the yin and yangAfter they determined that the interaction of the yin-yang two polarities is fundamental to the cosmos, the Chinese reasoned that they should apply the same principle in the development of their culture. This would ensure that their civilization would be in sync with the Tao. Hence the Chinese classified all aspects of existence as yin or yang polarities: Heaven (the sun) and Earth, male and female, growth and decay, high and low, space and time, advancing and retreating, something and nothing, active and receptive, movement and rest. All aspects of Chinese culture were informed by the yin-yang polarities: architecture, art, philosophy, statecraft, dietary habit and medicine, and, most pervasively, its Confucian social structure.

Confucius added the eight family members as attributes to the Eight Trigrams, embedding human life in the yin-yang cosmology.

Confucius studied the I Ching his entire life. He wrote explanatory texts for the cryptic language of the original corpus of the book and used it as the basis for his social construct. He added the eight family members as attributes to the Eight Trigrams to "embed" society in the yin-yang cosmology of the I Ching. The Confucian Middle Way became the norm in all aspects of Chinese society, both public and private. Personal life:Self-Interest (Yin): Prioritizing oneself can harm relationships and social harmony. Altruism (Yang): Excessive self-sacrifice might lead to neglect of personal needs and burnout. Middle Way: The Confucian middle path is based on reciprocity (shu), where one seeks mutual benefit and fairness. Continuity:Tradition (Yin): Rigid adherence to tradition can hinder progress. Innovation (Yang): Excessive innovation without respect for tradition might lead to chaos or loss of identity. Middle Way: Confucius advocates maintaining core ethical values from tradition while being adaptable and open to necessary change. Governance:Authority (Yin): Overly strict leadership risks alienation and resentment. Benevolence (Yang): Overly lenient leadership might lead to disorder or loss of respect. Middle Way: A leader should exercise a balance of firmness and compassion, ensuring justice while maintaining the trust and welfare of the people. The Confucian Middle Way is the way of qi, the path between the yin-yang polarities. When the polarities are in balance, society is in equilibrium, and frictional loss will be at a minimum. Unity of the physical and metaphysical Mynah, by 13th-century artists Mu-Qi: Gestalt avant la lettre. The Chinese notion of qi does not easily fit into Western categories. Scholars have long debated whether qi should be understood metaphorically, spiritually, or as a physical phenomenon, or all of the above. But art gives us an intimation of how the Chinese approached qi. The aim of the classic Chinese artists was not to depict a specific landscape. Rather, they tried to convey the notion of Dao through the interaction of yin and yang. The classic Chinese landscape typically depicts an idealized landscape with water (yin) streaming from mountains (yang). The Chinese Chan (Zen) masters zoomed into nature but also applied the yin and yang principle. In the classic masterpiece from Mu-Qi, the concave-shaped trunk (yin) and a convex-shaped branch (yang) set up tension (qi) in the composition. When we cover the branch at the top of the painting with our hand, the yin-yang balance collapses. The qi disappears. In modern times, the notion of qi has been influenced by science, cultural shifts, and global perspectives. It has evolved from a fundamental cosmological force in ancient China to a versatile concept encompassing health, ethics, spirituality, and science. As we noted above, Western thinkers like Habermas, Wilber, and Thompson offered a more secular approach to spirit, and a more "holistic" and humanistic worldview. Thompson went a step further and argued that Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching offered a path forward to a new planetary culture. Among the reasons he gave:

Thompson stressed the need to reconcile opposites in all aspects of life: human and nature, heart and mind, spirit and matter, male and female, East and West, freedom and responsibility. The yin-yang system is neither dogma, ideology nor religion, but "merely" a way of looking at the world. It identifies and reconciles perceived dualities and can be applied to all aspects of life. As Confucius would say: Don't be progressive or conservative; be both; NoteWith thanks to Bill Kelly (A New World Arising) |