|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected] Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD

The spiritual descent of Lucifer into Satan is one of the most famous examples of hubris.[1]

An Integral JourneyFrom hubris to HumilityJoseph Dillard

Developing humility is not automatic; it is a sophisticated skill set associated with wisdom, acceptance, witnessing, non-personalization, and inner peace.

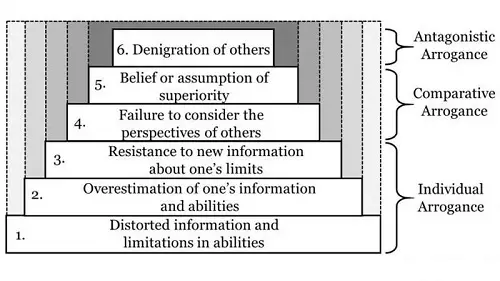

A classical example of hubris is provided by John Milton in his Paradise Lost.[2] Lucifer attempts to compel the other angels to worship him, and is cast into hell by God and the innocent angels, proclaiming: "Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.” hubris denotes overconfident pride combined with arrogance and describes a personality quality of extreme or foolish pride or dangerous overconfidence.[3] It often indicates a loss of contact with reality and an overestimation of one's own competence, accomplishments or capabilities. While hubris is often linked with a lack of humility, it can also be associated with ignorance. The Dunning-Kruger Effect, which describes a cognitive bias in which we mistakenly assess our intelligence to be greater than it is, is a profound and extremely common example of hubris as ignorance. We first “climb Mount Stupid,” as part of a normal learning curve, not knowing how much we do not know, and therefore infused with genuine but superficial over-confidence. The Dunning-Kruger Effect is related to the cognitive bias of illusory superiority and comes from our innate inability to recognize our lack of ability. We don't know how much we don't know. As we shall see, the Dunning-Kruger Effect is much in evidence within Integral. Nelson Cowan, professor of psychological sciences at the University of Missouri, led a team of researchers that has differentiated three types of hubris as arrogance:[4]

It is important to understand these three varieties of ignorance and be on the lookout for them first in ourselves, secondly in others, and thirdly within the Integral community, primarily because they undermine our credibility and trustworthiness, as well as that of Integral, in the eyes of others. Do we find examples of these varieties of arrogance in integral? Individual arrogance in IntegralIndividual arrogance is in evidence in integralists when we have an inflated opinion of our abilities, traits, or accomplishments compared to the truth. There are three varieties of individual arrogance to be on the lookout for: Distorted information and limitation in abilities: In addition to identification with high development on the cognitive line, Integralists are likely to also have high development on the line of spiritual intelligence as the result of life-transforming mystical experiences of oneness. Such experiences reveal not only personal truth and reality but a compelling conclusion that we now have experienced Truth and Reality, that is, we know not only what is real and true for ourselves, but for everyone. Consequently, these exceptional experiences on the line of spiritual intelligence can easily translate into “I am exceptional,” reinforcing our identification with a highly developed cognitive line, and generating individual arrogance. Mystical openings thereby produce distorted information, in that we commonly conclude what is true for us is universally true for all, leading to developmental imbalances, such as favoring philosophical and transpersonal relational exchanges over those that ground, support, and trap ourselves and others, such as relational exchanges of food, safety, sex, status, and power. Overestimation of one's information and abilities: Individual arrogance is commonly associated in Integral AQAL with high development in various lines, but particularly those of cognition and spiritual intelligence. In Integral, “the cognitive line leads,” meaning that self development is a process of objectification, awareness, and understanding, manifested as an expansion of world view, along with advances of the self-system line. To understand Integral AQAL means to access a multi-perspectival cognitive understanding, associated with “vision-logic” or “aperspectival-integral” awareness. Wilber describes this as the first level that doesn't view any level as superior, but instead recognizes the developmental necessity of each and every level. What typically happens for all of us, not just integralists, is that strong lines race ahead of weak ones. This is because we value excellence and invest not only our time and effort but sense of self in our strong lines, thereby ignoring or minimizing the importance of our weak lines. Morality, in the form of respect, reciprocity, trustworthiness, and empathy, and manifested as humility, can easily fall behind. Because we are largely our thoughts, when our thinking is multi-perspectival, it is easy to conclude that we are multi-perspectival or, that as an individual, we have attained to vision-logic in our self-system line and overall self development. Problems with individual arrogance arise when we identify with our high attainment on the cognitive line. If our world view is vision-logic, we may conclude that our self development is stabilized at post-late personal, even if our individual psychograph indicates lagging lines. It is only when lagging lines are core lines—cognition, self-system, morality - that tetra-mesh and evolution from level to level is hindered. If one of these core lines is fixated or unable to move permanently to dialectic synthesis, there is no balance among the four quadrants. The result is a failure to tetra-mesh, or advance from level to level. However, if we are strongly identified with the cognitive line, as most integralists are, the comfortable delusion of our self-assessment outweighs any objective assessment of our level of development. A very realistic consequence is hubris. Resistance to new information about one's limits: This identification with the lines of cognition and spiritual intelligence, combined with our conflation of moral intention with behavioral ethics, causes us to “climb Mount Stupid” regarding our level of development. We do not know what we do not know, per the Dunning-Kruger Effect. What we don't know is how out-groups view our morality. We stay resistant to knowing this because to become aware creates unbearable cognitive dissonance. Ignoring our complicity in the crimes and abuses of our in-groups allows us to maintain exceptionalism while remaining convinced that we really are moral, and that our core moral line has tetra-meshed right on up to vision-logic, if not higher. Individual arrogance of these derivations can show up in Integral as various forms of grandiosity. A very common one is the inflation commonly associated with having experienced mystical experiences of oneness; these are bad enough, but when combined with precocious intellectual development the overall impact is of people who have no clue just how far from the truth their identities have wandered. This is the case in at least three areas, justice, in which integralists believe that they represent justice when they ignore abuse and/or vote for “the lesser of two evils;” think they have and know Truth and Reality for and of others; and believe that due to their intellect that their world view is superior. Challenging these assumptions can easily threaten the identity of Integralists. Comparative arrogance in integralWhen Integralists display an inflated ranking of their own abilities, traits, or accomplishments compared to other people they are manifesting comparative arrogance. Failure to consider the perspectives of others: While integralists pride themselves on being multi-perspectival and considering the perspectives of others, the operative question is, “How do outgroups, that is, those who do not share our world view or perspective, view us, and why?” The typical response is to dismiss outgroup differences as uninformed, unenlightened, or malicious. But what if none of those possibilities apply? What if integral is simply irrelevant to their day-to-day needs? For example, people who have to spend all their time making ends meet do not have time for philosophy or transpersonal relational exchanges. They are more likely to be focused on the relational exchanges of wealth (in the sense of food and shelter), safety, sex, and status. What if their world view simply clashes with that of integral and they prefer their own? For instance, evolutionary scientists are unlikely to agree with Integral's “Eros as Spirit-in-action” model of evolution. Does this mean they are materialists or “flatlanders?” Or could those possibly be epithets that do not accurately portray their actual world view? The problem for some integralists is that to consider the possible legitimacy of a genuinely outgroup perspective is likely to stir up cognitive dissonance because it challenges a world view with which they identify. Arrogance, generally neither recognized nor acknowledged, can thereby be viewed as a protective defense to reduce cognitive dissonance. Belief or assumption of superiority: Mystical experiences of oneness often reveal not only a personal sense of truth but a sense of the Absolute as Truth and Reality. That is, a certainty that I know not only what is true and real for me but what is the Truth for everyone and what is Real for humanity. History is full of examples: “I am the way, the truth, and the light. No one comes to the Father but by me.” These claims can appear grandiose to others and arrogant in that they presume to know what is true and real for us as in, “I know who you are; I know what you need; I know what you need to do.” This is a belief or assumption of superiority, often hidden, but which can still be present in integralists. As we have seen, authentic excellence on various lines, such as those of cognition and spiritual intelligence, generates authentic superiority which is itself validated by peers and authority figures with the relational exchanges of elevated status and associated benefits. We identify with our areas of authentic superiority because they increase our confidence and validate our choices and world view. We ignore, minimize, or disidentify with our areas of authentic deficiency because they remind us of our inferiority, inadequacy, incompetence, ignorance, and stupidity. Therefore, we naturally become increasingly out of balance—building our strengths while ignoring our weaknesses. The more we do so the more likely hubris is unavoidable. Integral AQAL is hardly so overt in its comparative arrogance. Instead it merely claims that if 10% of the population adopt Integral AQAL that a global utopian transformation will occur. Is this only grandiose, or is it grandiose and arrogant as well? AQAL's notorious use of color jargon to rank people, societies, and groups typically is based on the premise that AQAL's ranking is superior because it includes not only all ranks, but all other forms of ranking. While such ranking can be useful and important, it easily leads to comparative arrogance. Colors and color jargon generates an ingroup culture that separates integral “initiates” from the illiterates. Despite loud protestations that this is not the intent, this practice generates hierarchical determinations of value among groups and with the individuals in those groups. There are indeed benefits in getting clear on these intellectual distinctions, and those benefits have to be weighed against the costs to personal relationships when the result is that we are seen as arrogant. When Integralists make Ad Hominem attacks they are also demonstrating comparative arrogance. By denigrating the character of others we are implying the superiority of our arguments, and by inference, ourselves. Antagonistic arrogance in integralDenigration of others: The denigration of others by some integralists is based on an assumption of superiority. “Denigration” is a strong but accurate word, which refers to “the act of making a person or a thing seem little or unimportant.” Synonyms include belittlement, depreciation, derogation, diminishment, disparagement, and put-down.[6] Denigration is closely associated with Ad Hominem, perhaps the most common and most primitive of all logical fallacies, employed when we run out of arguments against the other person's position and so instead attack them personally. As such, Ad Hominem is character assassination in formal attire, pre-rational emotionalism masquerading as intellectual sophistication, as if ridicule was an indication of superiority, exceptionalism, or intelligence. Antagonistic arrogance is the most abusive and overt form of hubris, but it may also be the most honest variety, because it makes no bones about saying what we hear implied: “You think you are superior to me.” This is most clearly seen in Ad Hominem attacks and global labeling. While the first is a logical fallacy in which we attack the person instead of the argument, the second is an emotional cognitive distortion in which we insult others, often in a stereotypical way. Both terminate communication, because they announce an unwillingness to continue to reason. They say, “I know I am right and I am not going to listen to what you have to say. So fuck off.” Accessing authentic humilityCognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), perhaps the most validated form of psychological intervention presently available, is based on the idea of first recognizing our cognitive distortions and then replacing them with more realistic and adequate perceptions. In CBT, thought embodies feeling, so to change our thinking is to change how we feel. However, arrogance goes deeper than mere feeling, because it is not only a feeling, but a judgment and intent that is designed to protect our sense of who we are by defending our world view when we feel it is threatened or under attack. Therefore, to counteract arrogance or hubris, we require a deeper level of intervention than normal cognitive substitutions, such as replacing the thought, “I am a failure,” with “I fail at some things and succeed at others; what I do is not who I am.” hubris is an over-valuing of the self. It requires the substitution of a realistic valuing of who we are. How do we know what a realistic value of who we are is? We don't; we probably never will because it is subjective and changes based on particular relationships and circumstances. All we can do is combine exterior and interior forms of feedback with our common sense and make the best determination that we can. However, it is realistic to consider that we will err in our estimation of who we are in at least two fundamental ways: we will over-value ourselves based on our strengths and under-value ourselves based on our weaknesses. Most of us spend our entire lives attempting to run away from our fear that who we really are our various weaknesses, gripping ever more tightly our sense of false security from identifying with our elevated lines, including those of cognition and spiritual intelligence. The result of this natural tendency is to lack any realistic conception of what humility is. Because we ignore our weaknesses we never develop a realistic humility regarding them. Because we over-identify with our strengths, our compensatory sense of superiority not only prevents us from accessing authentic humility but doubting that other people do as well. It is therefore important to differentiate inauthentic from authentic humility. False humility says, “Respect me because I am a good person.” Philanthropy and public service, when carried out as forms of virtue signaling, are indications of false humility. In contrast, authentic humility says, “I respect you because it is in my own best interest.” “This is because how I am treating you is how I am treating those aspects of myself that you represent. Since I want to like myself and avoid internal conflict, I choose to treat you well.” While this may be criticized as a selfish motive for humility, it is also pragmatic, resembling assertiveness in that it takes both the needs of both others and oneself into account. False humility says, “I am no threat to you.” Authentic humility says, “You may attempt to manipulate or take advantage of me due to your perception of my humility as a sign of weakness, but it would be a mistake for you to do so.” False humility makes attainment and success priorities, such as high development in various developmental lines. Authentic humility makes balance and ethical behavior priorities. False humility subordinates the self to the priorities of others. Authentic humility subordinates the self to the priorities of one's life compass.[7] False humility often involves self-deprecation, either out of a sense that we deserve it, or the false belief that “whipping the mule” will make it go faster, or to appear appropriate docile and obsequious before others. Authentic humility doesn't have anything to do with the ability to suffer humiliation, nor is it selfless, instead using the self as a tool rather than as a locus of identification. As such, a humble self is largely transparent and non-personalizing. While there tends to be a correlation between the intensity with which you need to defend this or that sense of who you are and hubris, there is an inverse correlation between strong investment in a sense of self and humility. Humility has also been defined as an outward expression of an appropriate inner, or self, regard, and is widely viewed as a virtue centered in low self-preoccupation, or unwillingness to put oneself forward, but for reasons of maintaining clarity rather than for self-protection or to gain the approval of others. In the 4th century BC in China, Master Kung, known to us through the Latinized “Confucius,” defined humility as the cardinal virtue, a principle that has remained fundamental to Chinese society ever sense: Humility is the solid foundation of all virtues.

A challenge for integralists is to cultivate varieties of humility to compensate and substitute for each variety of arrogance: Individual humility involves a purposefully conservative opinion of our own abilities, traits, or accomplishments compared to our estimation of our strengths, erring on the side of recognition of the ability of our limitations to slow our development. This assumes an inventory of our limitations, including an inventory of our limitations in our ethical behavior, such as our ability to be swayed by role expectations and reinforcers, our cognitive biases, emotional cognitive distortions, and logical fallacies. Accurate information and abilities adequate for our needs: While it has never been easier to access information, determining its accuracy is another thing entirely, as many fact-check sites are controlled and slanted toward the benefit of special interests. We are drowning in information and many of us have learned to be skeptical toward what we read, hear, and are told. Having abilities adequate to our needs implies a realistic assessment of our strengths and weaknesses and remembering that a core ability is seeking assistance from those who are talented in areas where we are not or to ask for help with jobs that are too large to complete ourselves. People respect such realism and honesty, and many people are honored by a request that they help, even if they cannot or do not. A realistic estimation of the veracity and usefulness of information and of our own abilities: While the above emphasizes access to information and the development competencies, this aspect of individual humility emphasizes their usefulness. You can have tons of information that you find important that does not solve the problem or address the needs of the other person; you can have all sorts of personal strengths, but what matters is that you have the ones that are needed in a specific situation by a particular individual. If you don't, say so and help find those resources that do. Openness to new information about our limits: Integralists generally pride themselves on being open to new information. However, every world view has its limits and blind spots. For example, integralists can be blind to seeing the sacredness of a completely naturalistic universe that does not require any forces or beings outside of it in order to manifest and fulfill itself. Similarly, AQAL tends to favor the interior quadrants and their characteristics, particularly consciousness, thought, intention, and value over their concrete externalization in social relationships as justice, problem solving, scientific empiricism, and behavioral ethics. Recognizing biases intrinsic in our world view can help us to suspend our assumptions and be open to new information. This is a critical form of individual humility for integralists. Comparative humility is a cautious and conservative ranking of our own abilities, traits, or accomplishments compared to other people, remembering to compare our strengths to their strengths and our weaknesses to their weaknesses, not our strengths to the same characteristic in the other person, which may not be a strength for them at all. Comparative humility remembers that we never know when we will need some strength that another person has, that we currently do not and so minimize in importance. Consideration of the perspectives of others: While we all normally assume we are considering the perspectives of others, it is impossible to do so unless we are first aware of our biases, assumptions, and interpretations, and second, set them aside in a phenomenological gesture. Arrogance does not, will not do this, because it knows already; it believes that it knows best. Once we become self-aware of our filters and choose to lay them aside, the necessary third step is to ask questions to clarify and make sure we understand the perspectives of others. Respect is based on acknowlegement that we understand the perspective of the other person; it is not based on agreeing with it. Belief or assumption of equivalency of selves: The self can be usefully compared to air. Air is real, and it has properties, but we look right through it; we don't see air, yet it is a medium that makes sight possible. To give any ontological reality to air, or to make it analogous to spirit or soul or some other metaphysical self takes us away from humility because such assumptions undermine the transparency and clarity of the self upon which authentic humility depends. While emotions, thoughts, and actions are not equivalent and differ in value, ease, addictiveness, control, and other parameters, selves are conceptual constructs which we use to organize our lives, relationships, and exercise control over both. As the Buddha long ago taught, in his concept of anatma, selves are pragmatic delusions, like the sun rising and setting. If they were not, they would not be equivalent, because they would differ in this or that quality or attribute. The assumption that selves “have” attributes, such as thoughts and feelings, is itself a useful delusion, but one that blocks fundamental equivalency that is essential to authentic humility. Synergistic humility: “Synergism” is meant to indicate a dialectical integration of selflessness as thesis and others as antithesis. It embodies a respect for oneself based on transparency and clarity combined with respect for others, based on a recognition of their intrinsic, inestimable value. While whales are worth more dead than alive and humans are worth more as instruments of production than as individuals, humility is highly cautious about assessing value in instrumental terms. Synergistic humility does not ignore the weaknesses or arrogance of others; rather it respects them as dysfunctional varieties of strength. Another version of this dialectic is arrogance as thesis, false humility as antithesis, and humility as synthesis. Respect of others and that with which they identify: We can all state, in the abstract, that we respect others. What counts is to what extent and in what ways we actually demonstrate respect, as defined by the other, not by ourselves. This particularly holds true for outgroups, as it is much easier to show respect to those who echo our own values and world view than it is those who do not. In the present, throughout the West, and indeed, throughout the globe in countries where accepted models of governance and economic order are breaking down, people are polarizing into camps that do not respect each other. Instead of searching for commonalities to bridge differences, people are regressing to black and white prepersonal perspectives that embody arrogance and hubris. While this is an understandable response to the loss of economic and cultural security, it is hardly a healthy one, because it has nothing to do with humility. Respect for others is not to be confused with accepting behavior. Abuse, cognitive distortions, and logical fallacies are all to be identified, because if they are not, they make respectful relationships impossible. It is also necessary to respect those things with which others identify. For example, if a Jew, Moslem, or Christian identify with Judaism, Islam, or Christianity, we respect their ethnocentrism and identification with cultural life scripts, because they are aspects of their identity. However, if a Jew, Moslem, or Christian identify with abusive practices that violate national or international laws and human rights, as do Zionism, Salafism, and neoconservative Christians, disagreement is unavoidable and is not to be hidden, while refusing to make the disagreement about the other person, even if they are convinced you are personally attacking them. We cannot control how other people are going to see our intentions and motivations, but we can continuously seek feedback from exterior and interior sources of objectivity to determine whether we are fooling ourselves or not. We can't assume we are humble; humility is largely a determination that others make of us, and they, not us, determine whether we are falsely or authentically humble. In terms of integral, synergistic humility is probably associated with some of the following qualities:

These are abstract guidelines, but how might they look in practice for integralists?

Developing humility is not automatic; it is a sophisticated skill set associated with wisdom, acceptance, witnessing, non-personalization, and inner peace. The more that you practice identifying with the perspectives of outgroups, of those who either disagree with you or who do not share your assumptions and world view, the quicker you are likely to develop authentic humility. To point out that there is indeed arrogance in Integral and that it is in need of humility is to open oneself to charges of arrogance, superiority, exceptionalism, and hubris. But such conclusions likely grow out of a need to reduce cognitive dissonance, to generate rationalizations and justifications in order to defend a world view upon which we have based our sense of who we are. Separating authentic from false humility is not easy, and I do not claim to have succeeded. If we desire to find and embody the sacred, we can do worse than focus on cultivating authentic humility. NOTES[1] Illustration for John Milton's Paradise Lost by Gustave Doré (1866). [2] What follows in this essay will be of no interest or value to those who find no hubris or arrogance in Integral, or who do not see a need for Integral or integralists to incorporate a greater sense of humility. However, such a perspective opens itself to suspicions of arrogance, and I am assuming that it is better to err on the side of humility than hubris, as long as genuine humility can be differentiated from false. This is not always easy, and few of us consider ourselves arrogant. [3] “Definition of hubris”. www.merriam-webster.com. [4] Three types of arrogance: https://www.futurity.org/arrogance-classification-2190542-2/ [5] There are definitely universal and collective aspects to personal and private experiences, mystical and otherwise. The question is, "How do we get out of our subjectivity to validate the conclusions we reach about the universal and collective aspects of our mystical experiences?" This is difficult because mystics are typically convinced of the objectivity of their truth and perception of reality. Also, mystics often record analogous presentations of oneness, which is how the distinctions of nature, deity, formless, and non-dual mysticism came into being. The question though, remains that raised by Kant in Königsberg, in his "Critique of Pure Reason" in 1788: “How do we differentiate those necessary conditions or categories which enable us to perceive from things themselves?” “How is it possible to escape our own subjectivity?” Kant was not a solipsist; he definitely believed in exterior realities, but he very wisely pointed to the various unavoidable filters, such as space, time, causation, unity, reality, existence/non-existence, necessity/contingency, possibility/impossibility. Therefore, we need to be quite cautious in our conclusion that because multiple mystics over multiple centuries report similar experiences, that these are not due to the similarity of the construction of human minds and means of perception. This is the parsimonious conclusion, and therefore the one to rule out. So far, it has not been ruled out. [6] “Definition of DENIGRATION” www.merriam-webster.com. [7] “Life compass” is a specialized term used by Integral Deep Listening (IDL) whose exposition is beyond the scope of this text. Material explaining this concept can be found in Dillard, J. Integral Deep Listening: Accessing Your Inner Compass, as well as on the website, IntegralDeepListening.Com. Briefly, “life compass” is a hypothesized center of evolutionary autopoiesis that is represented by consensus perspectives and recommendations provided by interviewed emerging potentials.

|