|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

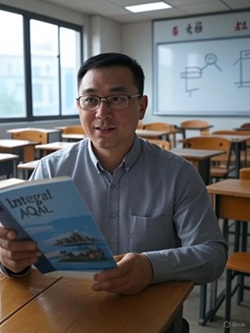

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected] Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD What Integral Can Learn from ChinaJoseph Dillard

If Integral is to become more than a map for a niche elite, it must do what China has done: translate worldview into real-world outcomes.

Wilber's Integral AQAL has not had the degree of influence in the world Wilber assumed it would have. This can be basically ascribed to its emphasis on ideas associated with liberalism (personal development) with a de-emphasis on collective human systems, such as subjugation of individuals and groups to international law, as well as an emphasis on the validity of individual experience (mysticism) at the expense of collective empirical evidence. What can integral learn from the Chinese model to balance and broaden its appeal?

Ken Wilber's Integral AQAL framework was designed to be inclusive and holistic, yet its actual cultural and geopolitical impact has been modest. In his 2020 lecture, “Liberalism and Nationalism in Contemporary America” John Mearsheimer explores the tension between liberalism and nationalism in the United States. His analysis has implications not only for the relationship between liberalism and nationalism in the U.S., but for 1) the relationship between Western liberalism and the “global south,” including China, and for 2) Integral and its traction on the world stage. Mearsheimer's argues that an overemphasis on liberal principles has led to a nationalist backlash. This is because liberalism prioritizes individual rights and universal principles while nationalism emphasizes collective identity and particularistic values. While these ideologies can coexist, an imbalance favoring liberalism can undermine national cohesion. After the Cold War, beginning in about 1990, the U.S. pursued policies promoting democracy and open markets globally. Domestically, there was a push for multiculturalism and open borders. This period saw liberalism overshadowing nationalism. The dominance of liberalism led to a resurgence of nationalism, exemplified by events like Trump's 2016 election and Brexit. These movements reflect a reaction against perceived threats to national identity and sovereignty. Mearsheimer contends that nationalism is a more potent force than liberalism. When liberal policies challenge national identity, nationalism tends to prevail. Similarly on a personal level, when acceptance of others leads to threats to personal security, self-interest tends to prevail. The implications for liberal democracies are that they must balance liberal and nationalist elements to maintain stability because an overemphasis on liberalism can lead to internal divisions and weaken national unity. This makes sense on a personal level as well. If we do not tend to our own security and safety we undermine our resources for helping others.

China's ascent on the global stage can be attributed to its adept balancing of nationalist and liberal elements. China fosters a strong national identity, emphasizing sovereignty and cultural pride. This nationalism underpins its domestic policies and international posture. Nationalism is given priority over liberalism, giving rise to it being called “authoritarian,” by the West, ignoring strong strains of nationalism and civilizational bias within the U.S and westerners. While maintaining political control, China has embraced market reforms to spur economic growth. This pragmatic approach allows for modernization without compromising national sovereignty. China was admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) on December 11, 2001, after 15 years of negotiations, largely based on the calculation that market reforms would subvert its nationalism. Because this is a case study of what “might makes right” in the hands of either liberalism or nationalism tends to do when threatened, and how it is self defeating, we can consider the dynamics of the WTO, the U.S. and China as a relevant case study. An Example of Self-Defeating Liberal Overreach: The U.S., China, and the WTOThe United States, EU, and other Western powers strongly supported China's entry into the WTO. They saw this as an economic opportunity, a belief that integrating China into global economic systems would generate internal reforms that would co-opt it into control by market capitalism controlled by Western interests, and therefore containment of China via engagement. The Western financial capitalist class began drooling over the profits from having access to 1.3+ billion Chinese consumers for Western exports, cheap labor and a manufacturing base for multinational corporations, with hopes to outsource industrial production to reduce domestic costs and increase corporate profits. Western companies willingly entered into agreements that surrendered their ownership of copyright and patent protections in exchange for entry into the Chinese market. All of these interests were pursued by Bill Clinton and his administration, as well as Bush II and Obama. There was the belief that integrating China into global economic systems would encourage market liberalization, promote “rule-of-law”reforms, that is, reforms favorable to invasion of western business interests, inside China, and eventually lead to political liberalization/democratization. This was a major U.S. foreign policy assumption in the 1990s. Membership in the WTO was also viewed in the U.S. as a softer, strategic effort to bind China to international rules to avoid future conflict. There were hopes that dependence on Western markets would moderate China's foreign policy behavior. This decision, to admit China to the WTO, will go down in history as a classic example of how hubris and greed can block objective analysis of an opponent's strengths and one's own weaknesses. This was the fallout: Starting in 2016-2017, under President Donald Trump, the U.S. began blocking the appointment of judges to the WTO's Appellate Body, which handles disputes between countries and requires at least three judges (out of seven) to function. As a result, the WTO collapsed in December 2019 when the number of judges fell below quorum. This was considered to be the better option for the U.S. because the WTO now threatened to make binding rulings that went against the economic interests of the U.S., undermining it as a tool for U.S. “might makes right.” The reasons that the U.S. gave for demolishing the WTO were transparently excuses and justifications for its true, underlying motivations. It accused the Appellate Body of exceeding its mandate by “creating new obligations” not agreed upon by member states, taking too long to issue rulings, and undermining U.S. sovereignty in trade matters. The U.S. recognized that WTO rules no longer effectively constrained massive Chinese subsidies of its businesses, its state-owned enterprises (SOEs), or “forced” tech transfer. The U.S. claimed that China was gaming the system while the WTO had no tools to enforce fair practices. More fundamentally, what was really going on was economic nationalism. The Trump administration, especially USTR Robert Lighthizer, wanted to reassert bilateralism over multilateral rules. WTO dispute rulings had consistently gone against the U.S., especially on steel tariffs, leading to the realization that the WTO was no longer an effective tool for asserting U.S. dominance in world trade and economic policy. This was occurring at a time when U.S. concern over China's rise as a tech and industrial superpower was increasing, BRICS was emerging as an alternative to Western-led institutions, Western manufacturing had been effectively outsourced to maximize profits through cheaper foreign labor, and there was a growing domestic backlash against globalization. While China's WTO accession was originally seen as a win-win economically and strategically by the West, when China adapted to the rules faster and more effectively than expected, while still protecting its sovereignty and state-led model, the West lost control of the game it created. In response, the U.S. and some allies began disabling the very global institutions they once championed. This is an example of how “might makes right” changes the rules of the game if it can, when it finds itself at a disadvantage. This is the conclusion of John Mearsheimer's geopolitical realism. We can apply it to a broader context by recognizing that this defensive reactiveness is somewhat a characteristic of human nature and therefore is to be expected of all nations, not just the U.S. or west. ImplicationsWith that background we can now turn to geopolitical implications of the contest between liberalism and nationalism and then to implications for Integral AQAL. Unlike Western liberal democracies, China avoids promoting its political system abroad, reducing resistance. While Western nations often promote liberal values universally, sometimes clashing with local traditions and nationalism, China engages with other nations through initiatives like the Belt and Road, focusing on mutual economic benefits. The Western approach can lead to resistance and diminish their influence in certain areas. Why doesn't the West stop doing so, since it obviously isn't working? An addiction to the effectiveness of centuries of “might makes right,” combined with exceptionalism and hubris, meaning blindness regarding the strengths of opponents and one's own weaknesses, are sufficient to explain why the West (including Israel) continues to engage in self-destructive behaviors regarding its opponents, including Russia, China, and Iran. Mearsheimer's analysis underscores the importance of balancing liberal and nationalist elements within a nation. China's rise illustrates the effectiveness of integrating national identity with selective liberalization, contrasting with the challenges faced by Western liberal democracies that prioritize universal liberal principles. This is where we can begin to see the affinity between Western liberalism and dysfunctional biases in the Integral AQAL model. One of the primary reasons the West is blind to the self-destructiveness of this imbalance between liberal and nationalist elements is its deep entrenchment in liberal Western values, particularly personal and spiritual development (Upper Left: subjective individual). Psychological integration is valued over collective integration and self-realization/enlightenment over humanism. For both Western liberalism and Integral AQAL, interior growth is viewed as the basis for external change. As a consequence, there is a tendency by both toward weak prescriptions for institutional or systemic design and reform. This is because strong enforcement of collective norms undermines individual freedom while increasing accountability and responsibility to others, transcending the priority of personal enlightenment. Meanwhile, China's model of development, with its synthesis of nationalism, Confucian collectivism, selective liberalism, and strategic pragmatism, offers practical lessons that Integral has tended to overlook. What Integral Can Learn from ChinaThis brings us to what Integral can learn from the Chinese model. In can strengthen the Lower-Right quadrant of social systems and institutions, reframe mysticism in service to the collective, rebalance liberal individualism with collective responsibility, build developmental metrics into power structures, and re-evaluate non-universalism. Let's look at the application of each of these. Regarding strengthening social systems and institutions in the LR quadrant, Integral AQAL would do well to recognize that while it describes how systems reflect stages of consciousness, it does not do enough to explain how to engineer those systems or hold power accountable. This underdevelops systemic implementation. In comparison, China's model prioritizes effective system design: massive infrastructure, centralized governance, strategic investment in key industries, and clear metrics for success. Integral would benefit from translating developmental insights into policy frameworks and institutional design, not just developmental maps or personal typologies. Regarding reframing mysticism in service of the collective, China's use of Confucianism as a civilizational ethos shows how a shared cultural-spiritual narrative can unify rather than fragment a people. By contrast, Wilber privileges states of consciousness (Upper Left), often sourced from Eastern contemplative traditions, but generally sees collective religion (Lower Left) as regressive (mythic). The necessary correction here is for Integral to emphasize shared myths, rituals, and cultural narratives that unite collective interiors (Lower Left) rather than just elevating individual spiritual attainment. It would also do well to abandon the elitist practice of viewing itself and the Western worldview as more highly evolved developmentally than other worldviews, including that of China. For example, labeling China “authoritarian” or “blue” are projections that do not reflect how the Chinese themselves or many in the global south view them. Regarding re-balancing liberal individualism with collective responsibility, the Chinese model integrates social harmony, duty, and responsibility into a working civic ethic, rooted in Confucianism and reinforced by the state, while Integral tends to lean toward Western liberalism: freedom, autonomy, self-actualization. The antidote here for Integral is for it to encourage a developmental ethic that includes obligations to the collective, not just rights of the individual, especially in education, governance, and civic participation. Regarding building developmental metrics into power structures, China doesn't claim postmodern or integral consciousness like Integral does, but it does implement policies based on adaptive, long-term thinking, such as 5-year plans, digital infrastructure, and local responsiveness to citizen complaints, which are encouraged. Basically, China focuses on insuring the stability of lower rung relational exchanges while the West tends to take them for granted, focusing on higher relational exchanges, like vision-logic cognition and worldviews. While Integral posits higher stages like Green, Teal, and Turquoise, it has little to say about how to integrate these into functional systems of governance, economy, or law. The result is a vacuum regarding transparency, responsibility, and accountability. Integral needs to translate stage development into real-time institutional policies and metrics of civic competence, perhaps akin to Bhutan's Gross National Happiness, but with real enforcement power. Regarding the re-evaluation of “non-universalism,” Integral assumes universal developmental trajectories, that is, the same stages, lines, and holons everywhere. In contrast, China's pragmatic, contextual approach does not seek to universalize its system, but rather localize adaptation based on context, history, and power balance. Integral needs to stop assuming every culture must “grow into” the same developmental mold. It can do so by endorsing polylateral evolution: different paths, different goals, same basic developmental principles.

If Integral is to become more than a map for a niche elite, it must do what China has done: translate worldview into real-world outcomes. That means addressing infrastructure, economics, governance, and collective identity with as much rigor as it addresses consciousness, compassion, and shadow. Only then can it compete as a viable civilizational operating system, not just a spiritual framework for the few. NOTES[1] This essay is amplified and supported by the input of Chat GPT.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|