TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Sheldrake RevisitedMore on Sounds, Fields and the Origin of FormFrank Visser

The hypothesis of “morphic resonance” comes across, not as a plausible theory, but as a confused metaphor.

Some years ago I wrote an essay comparing Rupert Sheldrake's theory of morphic resonance to the recent advances in "evo devo".[1] This scientific discipline links evolutionary theory to embryology, to understand how form is generated by gene regulation. In recent decades, much has been discovered about the way organs are shaped in a developing embryo, due to the discovery of a limited set of genes (the "genetic toolkit"), common to all living beings. I invited Sheldrake to respond, which he kindly did in a brief essay.[2] In this essay I'd like to revisit these topics, for I have continued my reading of both Sheldrake's and the evo-devo literature.[3] To freshen up your memory about Rupert Sheldrake: in 1981 he wrote A New Science of Life, which caused quite a stir in Europe and elsewhere.[4] Most famous is an editorial in the prestigious scientific journal Nature, which opined "This infuriating tract... is the best candidate for burning there has been for many years".[5] The author, editor John Maddox, concluded that the book should not be burned but placed "among the literature of intellectual aberrations". Of course, this helped greatly in turning Sheldrake into a hero of the New Age, which sees conventional science as an orthodoxy in itself, if not a religion of materialism. After this first publication Sheldrake has applied his concept of morphic resonance to wider fields of study, such as behavior, culture and religion. Not much has been heard of it in the field it was originally intended to illuminate: the origin of form in biological organisms.

Morphic resonance is a process whereby self-organising systems inherit a memory from previous similar systems. In its most general formulation, morphic resonance means that the so-called laws of nature are more like habits. (www.sheldrake.org)

It is said that the hallmark of pseudo-science is that one single concept is used to "explain" a huge variety of phenomena, ranging from atoms and molecules to culture and behavior. Sheldrake's hypothesis surely qualifies in that sense. But I don't want to go into that discussion here and focus on the field where the term "morphogenetic field" originated: developmental biology. Where most developmental biologists past and present take this as a kind of metaphor, Sheldrake is virtually the only one who has understood this to be a literal field, with real effects. It is this what sets him aside from the field of conventional (and unconventional) science. Briefly, Sheldrake posits the existence of "morphogenetic fields", which are responsible for the origin of form in biological organisms. According to Sheldrake, these fields are generated by other and older members of the same species and inherited by a process of resonance. This resonance should be distinguished from "energetic resonance", he explains, as in a tune-fork resonating with another tune-fork, producing the same tone, and is called "morphic resonance". This process is considered to be beyond time and space (and energy), and is often called "non-local". Sheldrake explains how a non-material process can have an effect on matter by likening it to the plan of an architect, which guides the manual labourers working in building the house. (Of course the architect's work takes energy as well, but that aside.) He adds that it is not his intention to claim that organic forms are the result of "conscious design", but just "to emphasize that not all causation need be energetic, even though all processes of change involve energy." (A New Science of Life, p. 71). One wonders how non-temporal, non-spatial, non-energetic "fields" can have material effects, to the degree that the highly complex organs of biological organisms are manufactured, without being the result of "intelligent design", but by "resonance" with older forms. How could resonance create forms? And how are these resonating influences created in the first place? Are organisms and their organs not only the result of morphogenetic fields, but also their source? Do we have any examples from science that could make this concept at least plausible? SOUND, FIELDS, FORMSSound can definitely create forms, as is perhaps best illustrated by a very famous historical example: the Chladni-figures created by the German physicist and musician Ernst Chladni (1756-1827).[6] On YouTube many examples can be found of how this works (and sounds), using modern technology. Here is one: We have here the following situation: There is no mystery here. There is a good scientific explanation for this phenomenon. In the case of Sheldrake's morphogenetic fields, however, we have an entirely different situation: So this metaphor doesn't help us understand morphic resonance. Biological forms are not known to produce sounds.[6a] Another area where we can see resonance in action is with two tune-forks, where one of them produces a sound, which causes a similar fork to resonate and produce the same sound (and not an other pitch). Again, here's an example from YouTube: Of course, Sheldrake has chosen resonance as metaphor because it conveys the idea of like-produces-like. A tune-fork can reproduce its sound in a similar tune-fork, and in theory this can be repeated with a third one, but on the whole the effect will soon die out. Not exactly what you want when you are looking to explain how species propagate and flourish. Even less so when the modus operandi behind morphic resonance is considered to be informational, and not based on energy exchanges. And affect future organisms—no matter where they are. We have here the following situation: Again, in the case of Sheldrake's morphogenetic fields, we have an entirely different situation: While sounds can clearly generate forms, under special conditions, and sounds can generate identical sounds through resonance, we don't know of any example were forms generate forms through resonance. The hypothesis of morphic resonance comes across, not as a plausible theory, but as a confused metaphor. Sometimes Sheldrake argues for the existence of fields with the example of a magnet. A magnet generates a field, which in turn can cause iron particles to take on various, often beautiful shapes. Here is again a random example from YouTube: We now have the situation: However, though a magnet definitely generates a field, the field does not generate the magnet. And therefore this metaphor can't be used to illustrate morphic resonance. Again, the metaphor breaks down when used to clarify the concept of morphic resonance or "formative causation". In the case of biological organisms or organs, there is no "magnet" anywhere around. Instead, the causality would work in the opposite direction: iron particles would created fields, which in turn would form other particles, anywhere in the world! Yet another metaphor Sheldrake uses is that of the radio or TV.[7] Just as a TV doesn't produce the programs it displays itself but only transmits them, forms don't produce themselves, as science assumes, but transmit influences from their morphogenetic fields. However, in the case of a TV set we have the following situation:

But in the case of a TV, the images/sounds are produced in a central studio and broadcasted by one or more send masts, which radiate electromagnetic signals in all directions. TV's within the range of that mast can receive the signals, and transform them again into the original images/sounds. In the case of biological organs or organisms, however, there is no such central broadcasting mechanism, but instead all TV sets are supposed to reproduce and pass on the signals they receive! Tuning in to a field is fundamentally different from being formed by it. In the case of biological organisms or organs, it would be as if the central broadcasting company would turn on the TV sets in the country and switch their channels! Again, a rather convoluted way of clarifying morphic resonance with mechanisms we do know that work, with the aim to explain why organisms tend to look like their ancestors. Incidentally, Sheldrake objects to the notion of "mechanisms", given his preference for an "organismic" or "holistic" approach but what is (energetic at least) resonance other than a mechanism? NOT EVEN A PLAUSIBLE THEORY?

The idea of resonance lacks the notion of guidance or genesis, in my opinion.

But assuming that morphogenetic fields do play a major role (other then genetic processes) in the origin of form, how would this work? Do they "mold" developing forms, so they don't exceed a certain boundary? How does such a field store all the relevant information which is needed to manufacture these delicate forms? How far and wide do these fields reach if they are not completely non-local? More importantly, since resonance works on the principle that like-produces-like, how can morphic resonance guide the whole process from cell to organism? Does every substage of this hugely complex transformation have its own field? And even then, how can such a substage-field move the process to the next substage at all? The idea of resonance lacks the notion of guidance or genesis, in my opinion. Science does have an idea about how this so-called "target morphology" would work, using the notion of cell memory instead of "field memory". Here's a fragment from A New Science of Life in which Sheldrake deals with these practical and pertinent questions: [A]ssuming that morphic resonance occurs only from past morphic units, and that it is not attenuated by the lapse of time, or by distance, how might it take place? The process can be visualized with the help of several different metaphors. The morphic influence of a past system might become present to a subsequent similar system by passing 'beyond' space-time and then 're-entering' wherever and whenever a similar pattern of vibration appeared. Or it might be connected through other 'dimensions'. Or it might go through a space-time 'tunnel' to emerge unchanged in the presence of a subsequent similar system. Or the morphic influence of past systems might simply be present everywhere. (p. 96-7)

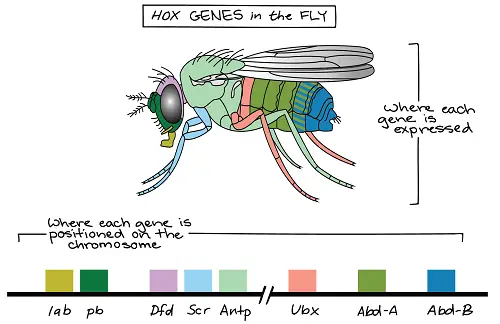

Isn't this all pure happy-go-lucky science fiction? Is it not unreasonable that scientists refuse to take these ideas seriously? More importantly, have they clarified anything in the field of embryology or developmental biology which couldn't be understood without the concept of morphic resonance? On the contrary, the field of evo-devo has resulted in massive amounts of data about these delicate processes, where morphic resonance has produced no new insights. More seriously, a recurring argument made by Sheldrake is that, since all cells in the human body contain the full DNA, DNA can't be responsible for the various cell types we have.[7] In the context of evolution: given the fact that we share the same fundamental so-called toolkit genes with insects and mice, genes can't explain the differences between these organisms. But the whole point of evo-devo is that we can go "form DNA to diversity"[8] by understanding the role of regulatory genes, which switch regular genes on and off, at different moments and in different locations. That is called "the Tool Kit Paradox" in Evo-Devo literature. It is a small leap from understanding how switches control development to anticipating how they have shaped evolution. Switches enable the same toolkit genes to be used differently in different animals. (Endless Forms Most Beautiful, p. 131) (Emphasis in the original) Sheldrake knows this, of course—though most of this research was done after his book came out—but why does he argue that something other than genes is needed to explain the differences between cells, organs and organisms? Is Sean B. Carroll, the popular spokesman on Evo-Devo, right that Sheldrake has "failed to grasp the essential idea of Evo-Devo—about the generation of diversity through changes in non-coding regulatory sequences."?[9] The stated goal of his own new theory, according to Sheldrake, is to be specific about its details: Any new theory capable of extending or going beyond the mechanistic theory will have to do more than assert that life involves qualities or factors at present unrecognized by the physical sciences: it will have to say what sorts of things these qualities or factors are, how they work, and what relationship they have to the known physico-chemical processes. (p. 11) It is exactly here, I think, that Sheldrake's theory has failed to live up to its promise—if it actually is a theory at all. Could it be that the long time rejection of his ideas by the large majority of scientists is caused, not by their ideological adherence to a materialistic and even "delusional" ideology, as he continues to claim[10], but by the fact they they could not make any sense of his concept of morphic resonance?

morphogenetic field The mediator of pattern formation and remodeling can be viewed as a “morphogenetic field” – the sum total of local and long-range patterning signals that impinge upon cells and bear instructive information that orchestrates cell behavior into the maintenance and formation of complex 3-dimensional structures (Source: Biosystems. 2012 Sep; 109(3): 243–261.)

A more conventional, recent definition of "morphogenetic field"

Ken Wilber has always supported Sheldrake's work[11] (as has Deepak Chopra, who has published his latest book in the US), I believe, because in the end these spiritual authors see evolutionary novelty as a transcendent phenomenon illusive to science. (Not many people realize that morphic resonance is supposed to deal only with the repetition of existing forms, not with the emergence of new forms). Science does claim it is on its way to explaining evolutionary novelty.[12] Says Carroll: We now understand how complexity is constructed from a single cell to a whole animal. And we can see, with an entirely new set of powerful methods, how modifications of development increase complexity and expand diversity. (Endless Forms Most Beautiful, p. 10) It is quite remarkable that Sheldrake's ideas have not only been rejected by conventional evolutionary biology, but are not even associated with post-Darwinian schools belonging to the Extended or "Post-Modern" Synthesis.[13] Has Sheldrake stepped outside of the boundaries of science altogether by holding on to an unworkable hypothesis? In the end Sheldrake is like the dualist philosopher of mind. No amount of brain modelling will convince him that consciousness has been explained. Likewise, no amount of genetic modelling will convince him that morphogenesis has been explained. Yes, we might have gone a few notches up the causal chain, in explaining the origin of form, but in the end the morphogenetic field will be waiting on the horizon. This makes his model fundamentally unfalsifiable—contrary to his claim that the hypothesis of formative causation can be tested—at least not in the field of morphogenesis. EVO DEVO MISUNDERSTOODIn his reply to my original essay Sheldrake did go into the matter of the extent in which the Evo-Devo research had made his theory of morphogenesis obselete. He didn't think so, of course, but the arguments given by him deserve further reflection. Though he correctly claims that the concept of morphogenetic fields itself dates back to the 1920's, just stating "evo-devo biology has led to a resurgence of the morphogenetic field concept" hides the fact that his interpretation of these fields differs widely from the contemporary understanding. He quotes from Sean Carroll, to substantiate this claim: "The concept of the morphogenetic field, a discrete set of cells in the embryo that gives rise to a particular structure, has held great importance in experimental embryology. The discovery of genes whose products control the formation and identity of various fields, dubbed 'selector genes', has enabled the recognition and redefinition of fields as discrete territories of selector gene activity." (Guss et al., 2001, Control of a Genetic Regulatory Network by a Selector Gene, Science 292, 1164-6) But indeed, this concept has been redefined by these researchers, as "discrete territories of selector gene activity"—not as free-floating morphic fields that are supposedly generated by every organism, to guide future organisms of the same kind to their proper shape. Sheldrake has disconnected the field from the organism, so to speak, and turned it into both a field formed by organisms as well as formative of similar organisms. This way, he has crossed a line of what is scientifically defensible. And though he is, again, correct to state that the discovery of the so-called Hox genes, responsible for the formation of organs within organisms, came as a huge surprise to many, because a wide variety of beings turned out to have idential Hox genes, this does not mean that Evo Devo has no answer to this paradox. On the contrary, by separating genes from regulator genes, this very paradox can be resolved: as Carroll said, it is not the genes you have that counts but how you use them. Sheldrake glosses over this important point by simply stating "Since these genes are so similar in fruit flies and in us, they cannot explain the differences between flies and humans." The genes may be similar, but the use they are put to is not, and that is a difference that makes a difference—both in embryology and evolution. Not convinced that this new science leads us anywhere, he optimistically presents his alternative: By contrast, my hypothesis of morphogenetic fields sees them as active fields of information that shape developing organisms. These fields inherit their own forms by the process of morphic resonance from past organisms. But there is no shred of evidence for fields that are both produced by organisms and that actively shape these same organisms in the way Sheldrake has in mind. Undaunted by this lack of evidence, he sees a way to connect these new discoveries to his own theory of morphic resonance: I see these switch genes as affecting the tuning system, causing an nascent embryonic structure to tune into one morphogenetic field rather than another, rather like a mutation in the tuning circuit of a TV receiver causing it to tune into a different TV channel. Apparently mutations are still needed, so organisms can tune in to different morphogenetic fields (how many of these fields are waiting to be discovered, and to what level of detail?), but wouldn't it be more in the spirit of morphogenetic fields if these fields actively cause these mutations? This leads to a quite weak interpretation of these morphogenetic fields, that supposedly do their mysterious work beyond the confines of time and space. To be honest, I can't see any way in which this could work. Does Sheldrake have any idea? Is resonance, in the end, not strong enough to accomplish this? Compared to the wealth of information provided by Evo Devo research on the way a limited set of regulatory genes functions as logical switches to create the wide diversity of forms, and has duplicated several times in the long evolutionary process, the theory of morphic resonance promoted by Sheldrake over many decades pales beyond recognition. As a random example of the expertise offered by Evo Devo, how about this? I would certainly not mess around with Giant and Kruppel if I were you!

Just as Hox genes regulate realisator genes, they are in turn regulated themselves by other genes. In Drosophila and some insects (but not most animals), Hox genes are regulated by gap genes and pair-rule genes, which are in their turn regulated by maternally-supplied mRNA. This results in a transcription factor cascade: maternal factors activate gap or pair-rule genes; gap and pair-rule genes activate Hox genes; then, finally, Hox genes activate realisator genes that cause the segments in the developing embryo to differentiate. Regulation is achieved via protein concentration gradients, called morphogenic fields. For example, high concentrations of one maternal protein and low concentrations of others will turn on a specific set of gap or pair-rule genes. In flies, stripe 2 in the embryo is activated by the maternal proteins Bicoid and Hunchback, but repressed by the gap proteins Giant and Kruppel. Thus, stripe 2 will only form wherever there is Bicoid and Hunchback, but not where there is Giant and Kruppel. (Hox gene, Wikipedia)

NOTES[1] Frank Visser, "Rupert Sheldrake and the Evo-Devo Revolution", www.integralworld.net, December 2013. [2] Rupert Sheldrake, "Morphogenetic Fields", www.integralworld.net, December 2013. [3] Sean B. Carroll, Endless Forms Most Beautiful, The New Science of Evo-Devo, Norton, 2005. This book has been a real eye-opener for me. [4] Rupert Sheldrake, A New Science of Life, 1981 (published in the US as: Morphic Resonance, Park Street Press, Revised and Expanded Edition, 2009). [5] John Maddox, "A book for burning?", Nature, 293, 245-246 (1981). Even the skeptical RationalWiki comments: "For any prospective future editors of prestigious journals, it was exactly how NOT to write a hatchet job review". See also: Adam Rutherford, "A book for ignoring", www.theguardian.com, Feb. 6, 2009. [6] "Ernst Chladni", Wikipedia. [6a] One can point to so-called biophotons, extremely weak radiation emitted by living systems, but it is unclear how this would perform the feat of morphogenesis, which works in the opposite direction. See "Biophoton". [7] "Morphogenetic Fields". Within the context of consciousness this is also called the "transmission theory": our brain doesn't produce thoughts, it only transmits them—presumably from a non-bodily soul or self. [8] Sean B. Carroll, Jennifer K. Grenier & Scott D. Weatherbee, From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design, Blackwell, 2001. [9] Personal communication by email, December 1st, 2013. Quoted in: "Rupert Sheldrake and the Evo-Devo Revolution". [10] Rupert Sheldrake, The Science Delusion, Coronet, 2012 (published in the US as: Science Set Free, published by Deepak Chopra, 2013). [11] Ken Wilber, "Sheldrake's Theory of Morphogenesis", offline on Integral Life, but available from Sheldrake's website. [12] Marc W. Kirshner & John C. Gerhart, The Plausibility of Life: Resolving Darwin's Dilemma, Yale, 2005. [13] See for example: Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (Wikipedia) and thethirdwayofevolution.com FURTHER READING

A brief video "What is morphic resonance?" created in 2014.

A TV documentary "Rupert Sheldrake, Heretic" made in 1993/4.

“Well, I thought I'd rather be a dissident...” |