|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).Forbidden BooksThe Cult of CensorshipDavid Lane

Say something cannot be read and you have automatically sparked an interest.

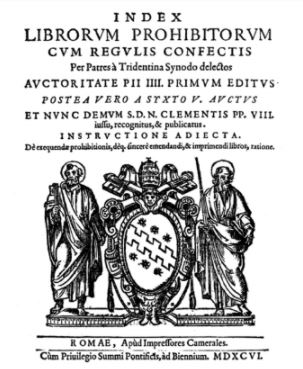

My father, Warren Joseph, loved books. He had an extensive library filled to the brim with works on science, literature, religion, and history. Yet, being a devout Roman Catholic, he took care not to have any books which were on the Forbidden Index as issued by the Church despite being a highly educated lawyer. Indeed, so cautious was he in his selection of encyclopedias that he wrote a letter to Monsignor Meade of St. Charles in North Hollywood seeking permission to buy a complete set of the Great Books of the Western World as published by Encyclopædia Britannica. Fortunately, his letter was forwarded to the Auxiliary Bishop of Los Angeles who, in a formal letter on October 27, 1958, granted my father permission to purchase the entire set with the caution that in reading some of the books on the Index he would not deviate from “the tenets of your faith.” As young students at St. Charles elementary school, we were oblivious of the Index of Forbidden Books, but we were keenly aware of the National Legion of Decency (later in the mid-1960s under the new title, National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures (NCOMP) since they rated movies from A (acceptable for general audiences) to C (condemned and sinful to watch). Each Sunday after Mass, a couple of my schoolmates would sell the weekly Catholic newspaper, The Tidings, which rated movies that were currently in theaters or coming out shortly. Naturally, we were always interested in seeing which films got the infamous curse of the C mark. As we went through the past records, we were shocked and amused that Son of Sinbad, a 1955 film adaptation from the Arabian Nights, was condemned and the Nuns at our school told us that we would commit a mortal sin by viewing it. Of course, this made me and my more mischievous friends more anxious to view it. The tragic thing in all this is that that the one thing that the Catholic Church should have expunged and condemned was how a number of young boys and girls were being emotionally and sexually abused by too many in the Church hierarchy. Yet, as we all know too well today, there was a concerted effort to cover-up and excuse such actions. Even in our local parish, there were two or three priests that were later found to be pedophiles and who were not brought to the proper authorities but instead transferred to another parish, only to continue their misdeeds. As a philosopher, what I find most disconcerting is how the Roman Catholic Church would ban Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, Rene Descartes' Meditations on Original Philosophy, and, most astounding, every book by the great Scottish thinker, David Hume. Whenever religious censorship raises its ugly head, one question comes to the forefront of my mind: What are they afraid of? Is Alexander Dumas' Three Musketeers so radical that it can shake one's faith to the core? What kind of belief system is this which can be so shaky and insecure that every book by Thomas Hobbes must be banned? My father Warren died when I was only seventeen years old so we never got the chance to discuss these controversial issues. I am not altogether certain he would agree with my harsh criticisms of organized religions, given his deep religious convictions. But to his great credit, Warren had an open mind and was not averse to discussing taboo topics with his kids. My sister, Kimball, who became an attorney, recalls having a civil conversation with our father about Bertrand Russel's widely read tome, Why I am Not a Christian, which is highly critical of many aspects of Christianity and its ethical system. Today, when I look back at religious censorship of almost any kind, it gives me a bad feeling of nausea, because such actions presume that humans are not intelligent enough to think for themselves through questionable ideas and their consequences in a rational and systematic way. To suppress contrarian ideas is the very antithesis of education itself. I realize that there many things we will learn in the course of our lives that will be upsetting. However, it is precisely in those moments where we go through the “fire of doubt” that we learn the most if we persist in our quest for truth or more robust forms of meaning. If we stop too early in our investigations (out of fear that we may be wrong or have to change our mind) we end up the losers in the process. Why? Because any knowledge or faith system should be able to easily withstand critical scrutiny. If it cannot, then that alone should reveal to us its weaknesses and why it is not worthy of defending. Yes, true education can hurt at times, but that is only because we are opening ourselves up to new and better forms of information. I remember how startled I was in 7th grade when my mother, Louise, who was a convert to Catholicism, lambasted Pope Paul VI who issued the papal encyclical entitled Humanae Vitae which condemned the use of a birth control pill as a mortal sin. My mother exclaimed to me, “That's just stupid. He doesn't know what he is talking about.” I was taken aback, since being indoctrinated since birth in Catholicism I thought the Pope somehow had a direct channel to God and Jesus. But my mother persisted, “The Pope is not infallible and, in this declaration, he is wrong.” At first, I tried to my best to defend the Pope, but clearly at that young age I was out of my depth. Months later I came to appreciate and admire my mother's heretical viewpoint and realized that she was indeed wise in not succumbing to authority for authority's sake.

As a Professor/Teacher for the past forty-two years, I have learned more from those who disagree with me and who hold contrarian positions than those who side with my opinions. Now, it must be admitted, that making a list of Forbidden Books makes such texts stand out all the more. It generates both controversy and interest. For instance, I remember when Martin Scorsese's film, The Last Temptation of Christ (based on the 1953 book of the same title by Nikos Kazantzakis) first came out in movie theaters in August of 1988. It caused a firestorm of protests because of the subject matter. Even those who had never read the book or seen the film argued vehemently that it should be banned from movie theaters. Ironically, all this bad press helped generate a bigger audience for the film, which drew mixed reviews, than it would have otherwise. I saw the film and liked it very much. The Jesus that is portrayed is a very human one, but also a very courageous one since instead of succumbing to temptation he eventually overcomes it. But orthodox Christians tend to only want their own sanitized version of Jesus to be allowed and all others to be disdained, forgetting that even Jesus' own close disciples had differing views on what he actually taught. The Catholic Church got rid of the Index of Forbidden Books in 1966 and no longer keeps a tally of what good Christians should or not should read. The reasons for this are manifold, but undoubtedly the evolution of communicative technologies and the freedom of individual expression has played elemental roles. In terms of pedagogy, telling a student she/he shouldn't read something because it is forbidden is actually a very clever way of generating interest that would be absent otherwise. I know from which I speak, since back in 1981 when I was teaching a section on sex education in my psychology course at Chaminade College Preparatory, a Catholic high in Woodland Hills, my students informed me that another older teacher who was also a priest in the Dominican order, had gone around his classroom and stapled a whole chapter of a particularly racy part together in each student's textbook. He told them in no uncertain terms not to read that “scandalous” section. My students then asked if I was going to do the same. I gave them an amused look and said, “Hell, no, that sounds like the most interesting chapter.” To which they applauded in cheers. However, I think in retrospect that the priest (whose name I have consciously let out) may have had the right idea, since I would imagine that his students' curiosity must have gotten the better of them and they may have pried open the “forbidden” section to have a peak. Say something cannot be read and you have automatically sparked an interest. Intellectual censorship only works temporarily, since the human mind is too inquisitive and too desirous of knowledge to let any door remain closed for too long. The mythic story of Adam and Eve and the Tree of Knowledge and Prince Agib and the 100th door are apt metaphors here and tell us much about humans and their insatiable appetite for something more.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|