|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).Bliss LandGlimpses of Cosmic ConsciousnessDavid Lane

The happiest moments of our lives, I suggested, was when we lose our sense of self, our sense of isolation, our contractedness.

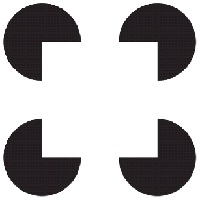

When my youngest son, Kelly, was four he used to ask the most intriguing and surprisingly mature philosophical questions. The one query, however, that made me think the deepest and the one that he cared most about concerned death and the afterlife. Kelly wanted to know what happened when we died. I had a number of options before me on how to respond. There was the materialist response which at first hearing sounds the harshest: “you become fertilizer.” Then there is the more clichéd reply, usually invoked by those belonging to Christianity or Islam, “good boys go to heaven or paradise.” Of course, there is always the most honest rejoinder: “nobody actually knows.” However, I didn't choose any of those answers. Instead, I said, “we all go to bliss land.” Kelly looked at me a bit incredulous, most likely because he didn't actually know what the term “bliss” actually meant. I then went on to explain my position. The happiest moments of our lives, I suggested, was when we lose our sense of self, our sense of isolation, our contractedness. I used surfing as my guiding metaphor to provide a more concrete illustration to my young son, who was also a budding water man. “Whenever I catch a good wave surfing or bodysurfing, I lose myself in the moment. I become keenly aware of the drop, the bottom turn, the throwing lip, and the projective line down at the shoulder. Without thinking, I became the process itself and time slows down and if I am lucky I get to tuck into a tube and see a cascading curtain of water envelop around me. It may last but two or three seconds, but because my awareness is right there and locked into the subtlest of blue and green textures and the rushing sound of vacuuming water, it has a timelessness to it. Kelly looks up at me, realizing that I got lost in my story telling, as I relived the many waves I have caught in my life. But he persists, “I don't get it, Papa.” I then tried a different route: “Kelly, when were you happiest?” It took him a few moments of reflection and he exclaimed, “When we went to Hawaii this summer.” “What was it about that trip that you remember?” “Ah,” Kelly recalled, “That's easy, it was when I saw the blue water for the first time and smelled the ocean. It was exhilarating. I was overwhelmed by the beauty of it.”  Sam Harris My son's reminiscence made me think of that famous episode in the life of the visionary mystic-saint, Sri Ramakrishna, who as a young Indian boy falls into a state of ecstasy while walking in a village field in Bengal, India, during the mid-part of the 19th century when all of sudden he sees a black rain cloud and then majestically a flock of white cranes flying in the sky. The juxtaposition of the two opposite colors was overwhelmingly beautiful. The very sight sent him into samadhi (divine ecstasy) and he fell unconscious. While my surfing adventures and Kelly's wonder at Waikiki gorgeous setting is not the same as Ramakrishna's samadhi, they do share something fundamental in common: beauty and our focused attention can awaken in us something utterly profound. It can be stated very simply, even if it sounds like a Zen Koan: we are happiest when we are not ourselves. That is, we feel the bliss of our existence when we are not trapped in our own narcissism. Sam Harris, the well-known neuroscientist who has written what I consider the most reasonable book ever published on meditation, Waking Up, makes a very cogent argument that what we believe to be our “self” is, on closer inspection, nothing but an evolutionary trick, an illusion without substance. In an interview with Gary Gutting, Harris explains his position by using a very clever visual illusion: G.G.: You deny the existence of the self, understood as “an inner subject thinking our thoughts and experiencing our experiences.” You say, further, that the experience of meditation (as practiced, for example, in Buddhism) shows that there is no self. But you also admit that we all “feel like an internal self at almost every waking moment.” Why should a relatively rare—and deliberately cultivated—experience of no-self trump this almost constant feeling of a self? S.H.: Because what does not survive scrutiny cannot be real. Perhaps you can see the same effect in this perceptual illusion:

It certainly looks like there is a white square in the center of this figure, but when we study the image, it becomes clear that there are only four partial circles. The square has been imposed by our visual system, whose edge detectors have been fooled. Can we know that the black shapes are more real than the white one? Yes, because the square doesn't survive our efforts to locate it—its edges literally disappear. A little investigation and we see that its form has been merely implied. What could we say to a skeptic who insisted that the white square is just as real as the three-quarter circles and that its disappearance is nothing more than, as you say, “a relatively rare—and deliberately cultivated—experience”? All we could do is urge him to look more closely. The same is true about the conventional sense of self—the feeling of being a subject inside your head, a locus of consciousness behind your eyes, a thinker in addition to the flow of thoughts. This form of subjectivity does not survive scrutiny. If you really look for what you are calling “I,” this feeling will disappear. In fact, it is easier to experience consciousness without the feeling of self than it is to banish the white square in the above image.[1] Whenever we look within to the source of our own consciousness we don't find it with a beginning or with an end. It just is. To rest in that very space, what the Buddhists have termed sunyata or emptiness, is to be free from the conceptual and limiting frameworks that arrest our awareness. This option is always with us and is never absent, even if it may be more difficult to access due to mitigating circumstances. The term cosmic consciousness is fraught with difficulties, particularly since there isn't a universal definition of what it actually means. However, for purposes of this edited book, I mean a transcendent experience whereby one is lifted out and beyond their normal waking state awareness, where one feels unbounded, liberated, and one with that which is trans-self, trans-personal. Richard Maurice Bucke (1837-1902), a noted psychiatrist from Canada, is responsible for popularizing the term "Cosmic Consciousness" when he wrote about the subject in a book of the same title that was published in 1901, just one year before his death. However, he apparently learned of the two-word phrase from Edward Carpenter (1844-1929), a radical thinker for his time who advocated vegetarianism, socialism, and Indian philosophy. Both used the term to denote a universalism, a leap beyond the merely personal, where one touched upon a realm above the merely finite. Of course, the conceptual idea and, more importantly, the very core of the experience, is not a new one since almost all cultures and all religions touch upon some aspect of “going beyond” one's self and experiencing the sacred. Rudolph Otto wrote a whole thesis on the subject in is his now justly famous and still widely read text, The Idea of the Holy, wherein he writes: “We are dealing with something for which there is only one appropriate expression, mysterium tremendum. . . . The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its “profane,” non-religious mood of everyday experience. . . . It has its crude, barbaric antecedents and early manifestations, and again it may be developed into something beautiful and pure and glorious. It may become the hushed, trembling, and speechless humility of the creature in the presence of—whom or what? In the presence of that which is a Mystery inexpressible and above all creatures.” I suspect we all have had mystical glimpses which we cannot codify into words. Some individuals, though, have had such numinous experiences that they go beyond the border of the normal or the expected and reach realms unseen and unheard by most of us. These include transformative near-death experiences, deep meditational transports, and the wildly unanticipated ruptures that occur randomly and seemingly out of nowhere, which happened to Ramakrishna as a young boy. Perhaps one of the most famous such awakenings occurred to Ramana Maharshi (1878-1950) of South India when he was just a teenager. Though his enlightenment appears to have been a permanent change and not a temporary insight. As Ramana recounted, It was about six weeks before I left Madura for good that a great change in my life took place. It was quite sudden. I was sitting in a room on the first floor of my uncle's house. I seldom had any sickness and on that day there was nothing wrong with my health, but a sudden, violent fear of death overtook me. There was nothing in my state of health to account for it; and I did not try to account for it or to find out whether there was any reason for the fear. I just felt, 'I am going to die,' and began thinking what to do about it. It did not occur to me to consult a doctor or my elders or friends. I felt that I had to solve the problem myself, then and there. The shock of the fear of death drove my mind inwards and I said to myself mentally, without actually framing the words: 'Now death has come; what does it mean? What is it that is dying? This body dies.' And I at once dramatized the occurrence of death. I lay with my limbs stretched out stiff as though rigor mortis had set in and imitated a corpse so as to give greater reality to the enquiry. I held my breath and kept my lips tightly closed so that no sound could escape, so that neither the word 'I' or any other word could be uttered, 'Well then,' I said to myself, 'this body is dead. It will be carried stiff to the burning ground and there burnt and reduced to ashes. But with the death of this body am I dead? Is the body 'I'? It is silent and inert but I feel the full force of my personality and even the voice of the 'I' within me, apart from it. So I am Spirit transcending the body. The body dies but the Spirit that transcends it cannot be touched by death. This means I am the deathless Spirit.' All this was not dull thought; it flashed through me vividly as living truth which I perceived directly, almost without thought-process. 'I' was something very real, the only real thing about my present state, and all the conscious activity connected with my body was centred on that 'I'. From that moment onwards the 'I' or Self focused attention on itself by a powerful fascination. Fear of death had vanished once and for all. Absorption in the Self continued unbroken from that time on. Other thoughts might come and go like the various notes of music, but the 'I' continued like the fundamental sruti note that underlies and blends with all the other notes. Whether the body was engaged in talking, reading, or anything else, I was still centred on 'I'. Previous to that crisis I had no clear perception of my Self and was not consciously attracted to it. I felt no perceptible or direct interest in it, much less any inclination to dwell permanently in it. It is here that we need to pause and be careful of how we classify such a diverse set of transpersonal experiences, since each are unique in their own way. To be sure, we can find commonalities, but far too often in our rush for a Huxley-like perennial philosophy we neglect the important biographical (and, it must be said, biological) nuances that flavor and shape one's numinous excursions. While many of us have had nature-related bliss moments (from surfing to mountain climbing to secluded walks in the forest), where we had ecstatic occasions, it may be too long a stretch to argue that these are on par with what mystics of time immemorial have described. Yet, I don't think the expansion of consciousness (cosmic or otherwise) is an either/or proposition but rather represents a continuum and that we do a disservice by collapsing such a spectrum of possibilities by prematurely categorizing them into pre-packaged theological overlays. They are part and parcel of what it is like to be a human being. How we ultimately interpret them (neurologically or religiously) is secondary to the value of the experiences themselves and what the wider aspects they offer us about our own self-reflective awareness. I must confess, however, that I do find that meditative practices, especially as developed in India which has a long tradition of allowing a fuller exploration of subjective states of being, to be of elemental importance in eliciting glimpses of higher, more far-reaching forms of consciousness. But meditation as a method is predicated upon how we focus our attention. Change our focus and we change the worlds we inhabit, at least in terms of how we subjectively experience them. The following volume is an idiosyncratic collection of personal reports which give but a peek into what has been poetically termed “cosmic” consciousness. Keep in mind, however, that not all noetic glimpses are the same since each represent different facets of what is mystically possible for us to achieve. Each in their own way provide a couloir into Bliss Land, a region that all humans desire and which given the right circumstances and conditions is available to every human being. It is not that the transcendent arrives after death (as in a heaven or a nirvana or paradise) but rather that it is always a current opening wherever we find ourselves. A drop in an ocean doesn't have to go anywhere to find the sea from which it arises. No, it simply looks within and surrenders to that ever-expansive mystery. It is also not an achievement of something or gaining or an adding onto reality. To the contrary, it our own nature that is forever there and as such is forever inescapable. Ramana clearly understood this secret of the bubble and the ocean when he wrote, “There is no greater mystery than this, that we keep seeking reality though in fact we are reality. We think that there is something hiding reality and that this must be destroyed before reality is gained. How ridiculous! A day will dawn when you will laugh at all your past efforts. That which will be the day you laugh is also here and now.” “Imagine that you are a bubble floating on the surface of an infinite ocean but that most of your life all you experience is the upper and outer reaches of that bubble. You never probe the depths from which you arise, which is a limitless expanse of the water that sustains you. If, for an instant, you get a glimpse of that fathomless bottom you would experience an unimagined expansion of being. It would have a cosmic dimension to it and your consciousness would be in . . . BLISS LAND.”

NOTES[1] Gary Gutting, "Sam Harris' Vanshing Self", opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com, September 7, 2014

Comment Form is loading comments...

|